Happy birthday, Salvador Dalí! Dalí is one of the best-known artists of the 20th century and standard-bearer for the surrealism style. And if you were to look up the word “weird” in the dictionary, the accompanying image should be of Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, 1st Marquess of Dalí de Púbol. And Dalí would probably be proud to be there.

Dalí was born in 1904 in Figueres, Catalonia, Spain to a middle-class family. He showed an aptitude for painting early on, creating skilled examples of impressionism, the groundbreaking style that presented outdoor scenes in soft, dreamlike sunlight and color.

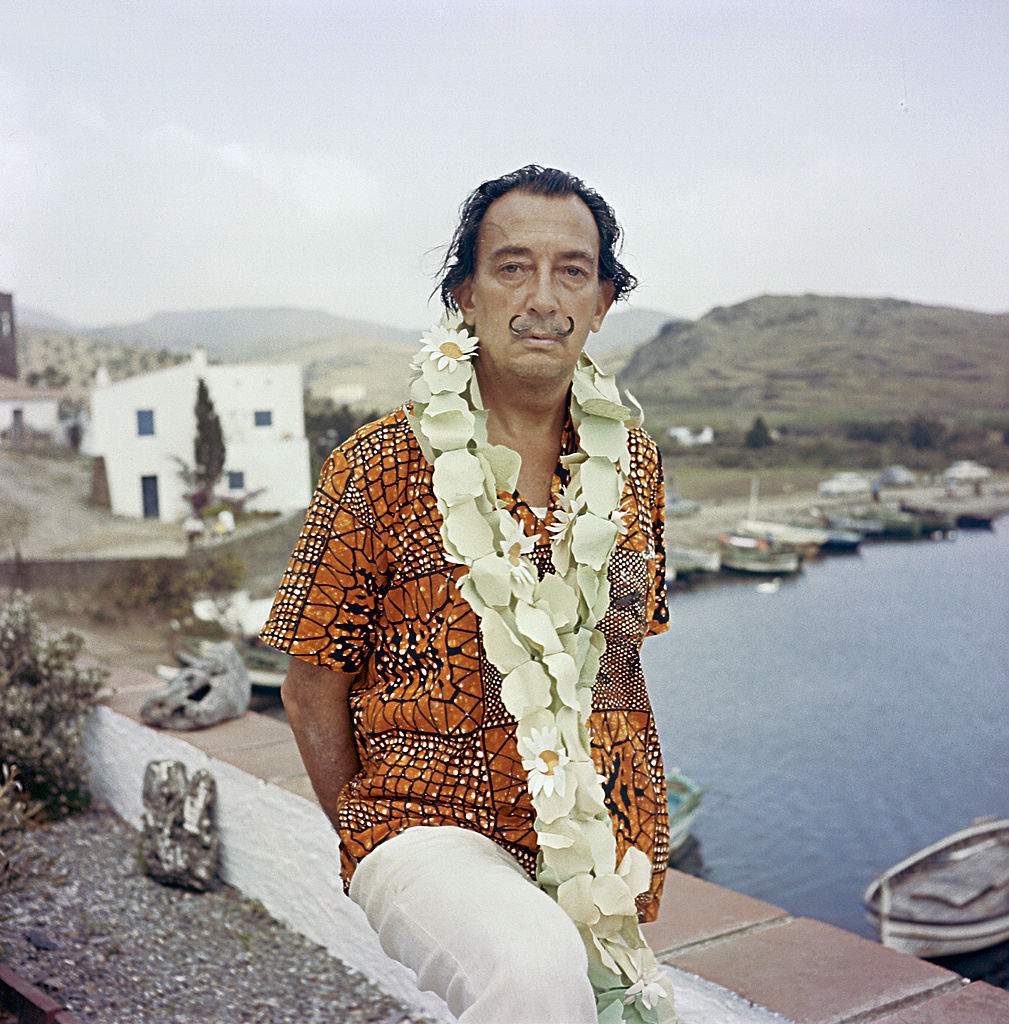

Salvador Dalí in Figueres, Spain - The artist in his home. Photo by KAMMERMAN/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Salvador Dalí in Figueres, Spain - The artist in his home. Photo by KAMMERMAN/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Amazingly, some of the earliest Salvador Dalí art survives, including “Vilabertrin,” a 1913 oil on cardboard landscape that Dalí created when he was around 9 years old. The location is the name of the piece, a Catalonian municipality. Soon after, at 14, he had his first art exhibition.

Believe it or not, the king of bizarre was seen as a shy and introverted child, though in his autobiography, he claimed to get attention in his secondary school by throwing himself down a staircase.

He and his family hung out on the rocky coastline of Cadaqués, a Catalonian town overlooking a bay on the Mediterranean. The scenery was incredibly formative on the budding artist, and appeared in many of his canvases. That terrain became a concrete force in his backgrounds.

His early personal life was marked by tragedy and discord. Dalí was close to his sister, and his mother doted on him, but his dad was a staunch disciplinarian, and the death of Dalí’s brother at just two years old cast a pall over the family. His mother died when he was 16, devastating him. Then, Dalí’s father married his mother’s sister soon after. Salvador surprisingly didn’t seem to mind. However, Dalí’s father knew talent when he saw it, and bolstered his son’s blooming art career.

Salvador Dalí went to college in Madrid, Spain, where he befriended future film collaborator Luis Buñuel. Dalí and his classmates followed the art movements taking place in Barcelona, Spain and Paris, where Dalí would admire and associate with art giant and cubism pioneer Pablo Picasso.

Dalí also closely studied the divisive theories of pioneering psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, a key figure for surrealists, due to his exploration of the unconscious mind.

His eccentricities in personal style started to emerge at this time, and he dressed like some bygone high-class individual in stockings and knee-breeches. One of Dalí’s eventual trademarks was his waxed, upturned mustache. At one point, the distinct feature approached 10 inches in length.

Salvador Dalí Holding Glass Walking Stick, Getty Images

Dalí’s sizable ego made one of its first appearances at the end of his college days in 1926. Right before final exams, he deemed his professors unworthy to critique his work, and he dropped out. Turns out, he may have been right, as Dalí was an exceedingly skilled artist, even at this early stage.

By 1929, Salvador Dalí was a member of the surrealist group. He would get their attention via a silent short film collaboration with Buñuel, titled “Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog).” This piece of cinema displayed “dream logic,” in its montage-like form. The chronology jumps around, and characters engage in nonsensical behavior while in odd garb. The most notorious moment is when Buñuel seems to slice a woman’s eye open with a razor (it was actually an animal eye).

Also, in 1929, Dalí first met Gala Diakonova, the woman who would become his wife, manager, and muse. This was the final straw for Dalí’s family. They were up in arms over the fact that Gala was 10 years older and had left a husband and child for him. His continued exploration of controversial subjects, especially religion, didn’t help either. The estrangement greatly hurt Dalí, but it wouldn’t stop him. Religion would be a go-to subject for Dalí throughout his life.

Focusing on Salvador Dalí’s striking finished products can obscure the way he got his ideas. Enter his “Paranoiac Critical” method, developed in the early 1930s. This process is considered his crowning theoretical achievement and the most important surrealist technique of all. The artist seeks to see several images within a singular image, akin the phenomenon of pareidolia, where one can see, for example, a cloud that looks like a human face.

To activate this state, Dalí induced paranoia within himself through sheer force of will. When he “came back” to the real world he would paint representations of what he perceived. The artist was basically putting himself at the intersection of rational and irrational, asleep and awake, in his production of what he called “hand painted dream photographs.” In this realm, Dalí found connections of disparate ideas and innovative ways of thinking. It was a shot in the arm for the then-floundering surrealist movement.

“Metamorphosis of Narcissus” (1937) is a characteristic example of Dalí in his “Paranoiac Critical” mode. The work depicts a moment in the story of Narcissus in Greek mythology. In a nutshell, Narcissus was super-attractive but rejected all suitors. When the nymph Echo was rejected, she wasted away to just a voice. The goddess Nemesis was miffed by this, so she had Narcissus stare into a pool and fall in love with his own reflection. Since he can’t embrace the reflection, he wastes away into the namesake flower.

In presenting the myth in his work, Dalí has doubled his primary representation of Narcissus staring into the water, with the mythological figure deconstructed into a series of shapes. Other elements of the myth make up the background. Dalí provides a hint for properly viewing the painting, stating, “If one looks for some time, from a slight distance and with a certain ‘distant fixedness,’ at the hypnotically immobile figure of Narcissus, it gradually disappears until at last it is completely invisible.”

“Metamorphosis of Narcissus” credit Bettmann / Contributor, Getty Images

In this period, he also set about identifying and codifying the concept of the “surrealist object.” Salvador Dalí saw such an object as “functioning symbolically” made from found or already-created items. The items were often not conventionally associated with each other, and Dalí felt that such objects could have positive or negative connotations, and reveal the desires of the unconscious. This idea famously took shape as “Lobster Telephone” (1936) and its five differently colored iterations.

Turns out, Salvador Dalí would be the one to create the most widely known work of surrealism with the 1931 painting “The Persistence of Memory,” featuring its highly memorable “melting clocks.” Worldwide acclaim has made the melting clock a motif that would appear on most of the merchandise types found in a typical museum gift shop. It was a compositional element that Dalí would revisit a number of times, significantly in the 1984 sculpture “Profile of Time,” which depicts a melted clock draped over a tree branch. A limited edition of 350 were cast in bronze, and they can be found tucked away in public spaces across the world.

Julo, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Speculation related to “Persistence” encouraged Dalí to insist that there are no hidden meanings in his work. The melted clocks are said to reference Einstein’s theories about the flexibility of time, but Dalí himself said he was inspired by melting camembert cheese. Assignment of meaning is something that stuck in Dalí’s craw. He didn’t feel anyone had the authority to assign a definitive meaning of a given piece of art.

Dalí had a rocky relationship with fellow surrealists. Insults and accusations began to be thrown, and controversial artwork created. Eventually, there was what was called a “kangaroo court” wherein Dalí was accused of fascist sympathies. Dalí thought it absurd, and set about making a mockery of the “trial,” pretending to be ill, and wearing too many clothes. He would be formally “expelled” from the group in 1934.

If Salvador Dalí was hurt by this, he didn’t show it, he went right on creating a spectacle wherever he went. His public acts became legendary. He entered the 1936 London International Surrealist Exhibition clad in a full diving suit, intending to dive “into the subconscious of the human mind,” and nearly suffocated. To commemorate his discovery of the “logarithmic curve of cauliflower,” he once showed up at a lecture at the Sorbonne in Paris with his car stuffed with 1,100 pounds of the vegetable. And that’s just scratching the surface.

In the end, no group could hold Salvador Dalí, he was a genre unto himself.

Unfortunately, the situation in Europe was getting dire. Dalí was caught up in the Spanish Civil War, which started in 1936. Though he escaped, an artist friend was executed, and Dalí’s own sister was tortured. Dalí would paint “Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War)” that same year, and front and center, dominating the canvas, is a giant, grotesque creature causing destruction—a metaphor for war.

After the start of WWII, Dalí and Gala decamped to the United States. Here, he became the main name and face of surrealism, outlasting all his European surrealist cohorts. He soon found himself in Hollywood. Dalí managed to meet iconic filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock, who asked for the artist’s assistance in creating dream sequences for his 1945 noir thriller “Spellbound.” Hitchcock was a fan, feeling that Dalí was the best man for the job of depicting the experience of dreams. Dalí even worked with Walt Disney at the time, though that project was shelved.

Salvador Dalí’s keen intellect came to the fore in 1950, when his interest in physics and molecular biology, along with his hope that science could find the truth about religion caused him to begin a “Nuclear Mysticism” phase. He was also impacted by the dual nuclear explosions that ended World War II. Dalí was inspired to reimagine “The Persistence of Memory” in this new phase with “The Disintegration of The Persistence of Memory” (1954). Elements that were once solid retained their overall shape, but became fragmented into tiny cubes, representing empty space present in atoms.

Unique self-portraits are a familiar sight in many Salvador Dalí paintings, such as 1941’s “Soft Self-Portrait with Grilled Bacon.” In it, the flesh of his flaccid melting face is held up by crutches, which symbolize grounding in the traditional real world, and support for inadequacies. Regarding his visage, Dalí felt that when representing oneself, the skin is most important, surpassing anything intangible, like spirit. In a tie back to the Old Masters, Dalí had seen Michelangelo representing himself as a piece of flayed skin on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, not unlike how Dalí depicts himself in “Soft Self-Portrait.”

“Dalí Atomicus” a 1941 photograph of Salvador Dalí by Philippe Halsman credit Wikimedia Commons

Philippe Halsman, the important mid-century photographer, Dalí collaborator, and surrealist co-conspirator managed to capture one of the clearest presentations of Dalí’s kinetic whimsy in the 1948 image “Dalí Atomicus.” Everything in the frame of the photograph is airborne along with the artist, including cats, cascading water and some of Dalí’s artwork.

Despite the ungainly title, 1976’s “Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean Sea which at Twenty Meters Becomes the Portrait of Abraham Lincoln-Homage to Rothko” painting is a latter-day Dalí masterpiece, showing that the artist still had it, even in his 70s. A copy even has a place of honor in the atrium of the famed Dalí Theatre & Museum in Figueras, Spain, overlooking the artist’s tomb. The genesis of “Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean Sea…” came with Dalí happening upon an article in “Scientific American” that featured an early computer-generated, highly pixelated, image of Lincoln’s face on an American $5 bill. The aim was to show how little resolution is needed to create a recognizable face, and it got Dalí’s wheels turning in a “Paranoiac Critical” way. The result is two images in one, a scene featuring muse Gala surrounded by heavily religious imagery, then, when the viewer squints slightly, the image of Lincoln appears. The “Rothko” reference in the title refers to the celebrated “color field” artist Mark Rothko, who tragically passed away a few years before the art was unveiled.

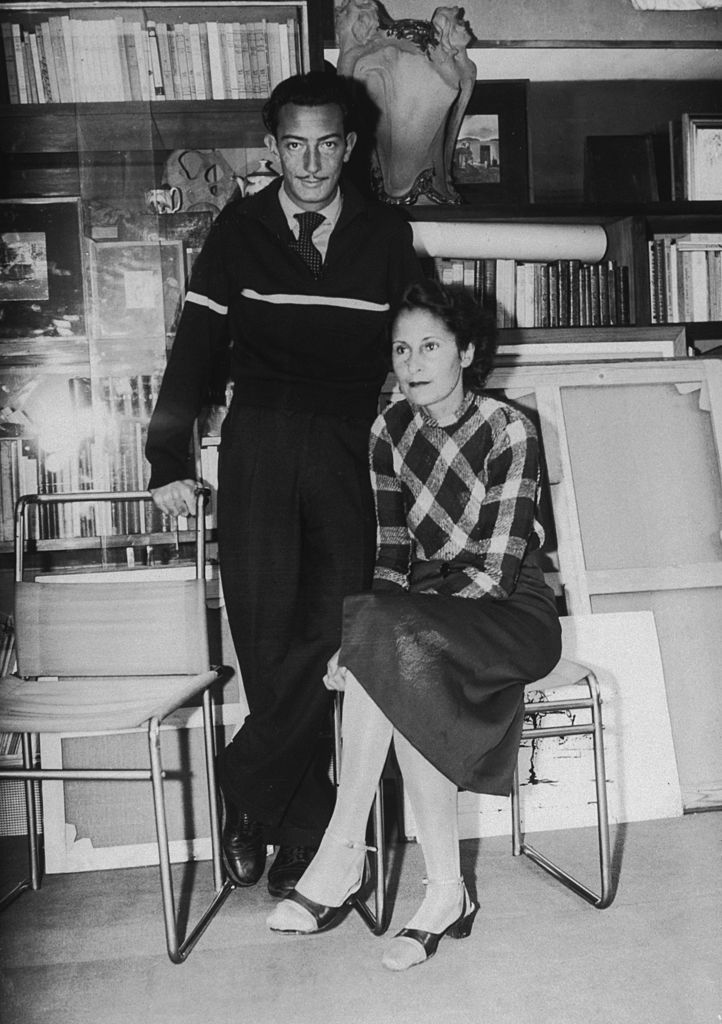

Spanish Surrealist painter Salvador Dalí (1904 - 1989) posing at home with his wife Gala (1894 - 1982), shortly before leaving for New York where he would be exhibiting his work, Paris, France. Photo by New York Times Co./Getty Images

Salvador Dalí died in 1989, aged 84. He was a true original, and since he was a bit of an artistic polymath, it takes whole books to cover everything he created. But in whatever style or medium, he has left the world a treasure trove of inspirational art. So, take a page from his book and don’t be afraid to get weird in your own work!

Are you feeling inspired after reading about Salvador Dalí? Are you ready to create something extraordinary? Make sure to shop the set below for your creation.