Buon compleanno Leonardo da Vinci!

This master has such an important place in history that we’ve declared it his birthday month. Da Vinci epitomizes the concept of the “Renaissance Man,” as someone who had an insatiable curiosity about a wide variety of disciplines throughout his life.

Leonardo da Vinci was born in 1452, in the area of the Italian city-state of Florence. He entered a world where there was much infighting throughout his area of Europe. It was a time when the God-centered Middle Ages was giving way to the human-centered Renaissance.

Da Vinci’s place in society should have limited him to a lowly existence. He was the illegitimate child of an esteemed notary and a poor farmer’s daughter. Being illegitimate, he could not inherit an estate, get into the family business, take his father’s name, or have his education funded.

When he was a teenager, Leonardo da Vinci relocated with his father to the bustling city of Florence. Here, he became acquainted with the wealthy, powerful banking family pulling all the strings: the Medicis. More importantly for da Vinci, they were the city’s foremost patrons of the arts.

In Florence, da Vinci knew what he had to do to raise his status in society—become a member of a professional trade union, known as a “guild.”

Leonardo da Vinci had two things going for him in this quest: painting talent, and his father’s connections. So, in 1468, at the age of 16, he became an apprentice at the studio of notable artist Andrea del Verrocchio.

Verrocchio had commissions aplenty in a wide range of mediums, especially from the Medicis, and it was here that da Vinci gained insight into the link between art and power.

The workshop was undertaking a major project right when da Vinci showed up, the creation of a two-ton copper ball that was to sit atop the city’s famed Duomo cathedral. Getting the ball in place was a mechanical engineering challenge, and in devising how this would take place, da Vinci’s interest in this branch of engineering was sparked. Leonardo became Verrocchio’s prized pupil, and by the age of 20, he finished his apprenticeship and officially joined a guild. Though he could now go off on his own and independently give people official Leonardo da Vinci artworks, he stayed with Verrocchio for a time.

From this period, we have what is considered the oldest surviving da Vinci painting, a collaboration with Verrocchio entitled “The Baptism of Christ,” completed c. 1475. The angel on the far left is attributed to da Vinci, and art historians point out his sublime depiction of motion in the being.

“The Baptism of Christ” by Andrea del Verrocchio and Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1475, credit Wikimedia Commons

Soon after, a complicated conspiracy, murder, and execution involving the pope, an archbishop, and rival families had Florence’s citizens braced for war. Florence’s army was overpowered by the army of Naples, led by King Ferdinand. So, Lorenzo de’ Medici was compelled to a face-to-face with Ferdinand, to broker peace.

Lorenzo succeeds, but it took Florentines three months to find out. In the tense wait, da Vinci turns his attention to something he would avidly pursue, designing tools of warfare.

Between 1480 and 1482, Leonardo da Vinci worked on what is now considered his first important piece, “The Adoration of the Magi.” It was commissioned by the Augustinian monks of San Donato a Scopeto in Florence. Da Vinci’s conception of this commonly depicted subject was revolutionary. Virgin and child appear conventional, but they are surrounded by a chaotic mix of devotees and horses. And da Vinci himself may be at the bottom-right.

“Adoration of the Magi” by Leonardo da Vinci, 1480-1482, credit Wikimedia Commons

Da Vinci worked diligently on it, but, as he did many times in his life, he left it unfinished, apparently losing interest. So many of what could have been significant Leonardo da Vinci paintings were not to be. In the real world, though, this tendency resulted in angry clients, loss of plum commissions, and lawsuits. Da Vinci’s aversion to completing his artworks has experts speculating that he had a mental illness, potentially ADHD or OCD.

Da Vinci grew weary of painting and wanted to explore other avenues, so in c. 1483, he moved to Milan. As the northernmost Italian state, Milan was especially susceptible to foreign enemies.

This meant heavy militarization and an abundance of weapons. Seeing an opportunity, da Vinci dispatched a letter to acting Duke Ludovico Sforza, in which he presented himself as a genius military engineer, only mentioning that he was a painter in the last line. He mentions plans for bridges, mortars, catapults, and other war tech. In these illustrations da Vinci revealed a fixation with size. For example, he designed a crossbow that was meant to be as large as a tractor-trailer.

But the Duke ignored the military part of the letter, and asked da Vinci to paint a portrait of his mistress. The resulting painting “The Lady with an Ermine” is groundbreaking—considered the first portrait to depict thoughts and feelings through posture and gestures. Something seems to catch her eye, causing her to turn to the right, and the animal’s muscles convey tenseness and alertness.

“Lady with an Ermine” by Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1490, credit Wikimedia Commons

Despite da Vinci’s initial ambitions not panning out, he sticks around. He knew that proximity to power could lead to opportunity. And he was right. The Duke commissioned a massive statue of his father atop a stallion, intended to be the world’s biggest equine monument. Da Vinci spent a dozen years conceptualizing the 24-foot-high statue, which was to be cast in 60 tons of bronze. Despite the completion of a giant clay model, military concerns caused that metal to be used for cannon-making instead.

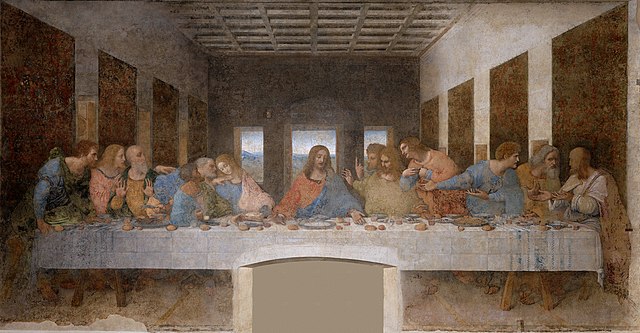

A different commission from Ludovico resulted in one of Leonardo da Vinci’s greatest paintings. It was for a mural at Santa Maria delle Grazie, the Sforza court church, and would be called “The Last Supper.” It depicts Christ’s final meal with the Apostles, at the very instant that Christ declares “one of you will betray me.” Da Vinci himself explained that the anguish of the assembled is being conveyed via distinct gestures and facial expressions. Unfortunately, da Vinci erred with his paint formulation, and the work began to deteriorate, necessitating frequent restoration efforts.

“The Last Supper” by Leonardo da Vinci, 1495-1498, credit Wikimedia Commons

The end of the House of Sforza came when Milan was invaded and occupied by the French. In the end, the giant clay horse was used for target practice. After 17 years, da Vinci left Milan, eventually moving back to Florence. Leonardo Da Vinci returned as the 1400s gave way to the 1500s, and he was feeling his age as he neared 50 years old. He soon became aware of a young, Florentine artist named Michelangelo Buonarotti. Though both would share status as masters, they really did not like each other.

Da Vinci would soon get a new patron, the notorious Cesare Borgia, one of the era’s shiftiest, shrewdest, blood-thirstiest individuals. Borgia, the illegitimate son of Pope Alexander VI, had control of the papal armies, and sought to use them to acquire large swathes of territory.

Borgia felt da Vinci could help him in his quest, so he brought da Vinci on as Chief General Engineer. It is thought that in this role, Leonardo da Vinci witnessed the horrors of war with his own eyes as he was embedded in the army. He oversaw construction of offensive and defensive fortifications and structures, along with weapons. The artist’s detailed maps were also invaluable when planning battles.

By 1503, da Vinci had departed Borgia’s orbit, greatly dismayed when the despot had one of the artist’s friends in the army executed.

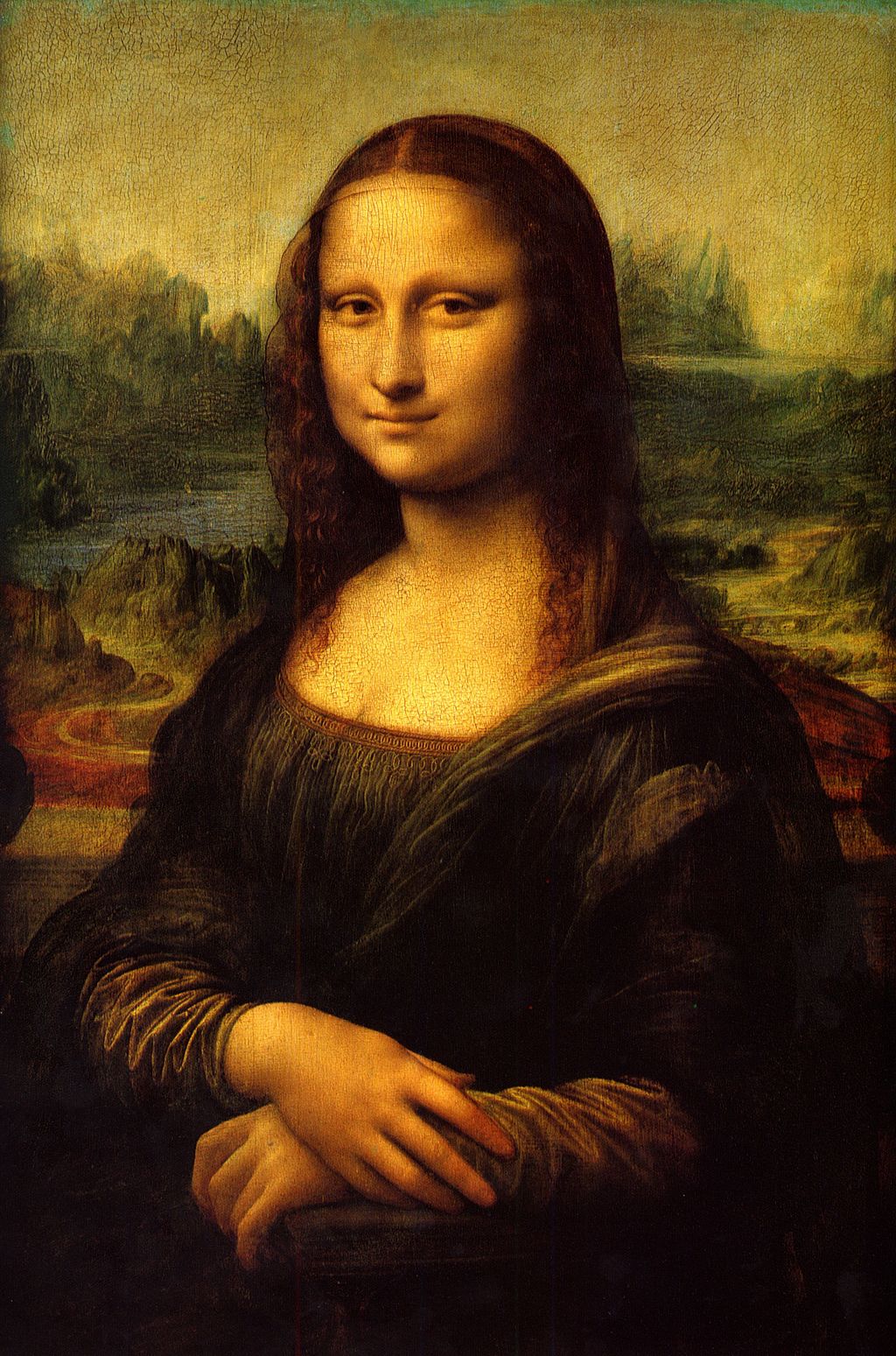

He settled down into a relatively peaceful life, and would create one of those Leonardo da Vinci artworks that needs no introduction: “Mona Lisa.”

“Mona Lisa” by Leonardo da Vinci, begun c. 1503, credit Wikimedia Commons

The sitter has never been identified, but theories abound: it is da Vinci’s lover, da Vinci himself, or the wife of a merchant.

Leonardo da Vinci’s formidable technique is on full display in this work. To the artist, faces look their best at dusk, and he created that atmosphere utilizing “sfumato,” a smoky effect. It requires paints with transparency, and a well-honed eye to pull off. Experts are awestruck by this demonstration of skill.

Another mystery is the coy quality of her smile, which is seen in the shading at the corners of the mouth and eyes—these happen to be the parts of the face that convey the most expression.

“Mona Lisa” was never completed, and da Vinci worked on it until his death. Who knows what it would have looked like if the artist had lived longer.

By the time of Leonardo da Vinci’s passing, he would accumulate 15,000 pages of writings and drawings, and what is immediately noticeable on the pages (besides the occasional shopping list) is the fact that the writing is backwards. Speculation brings up codes or secrecy, but a plausible explanation is that he was left-handed, so writing right-to-left made sense.

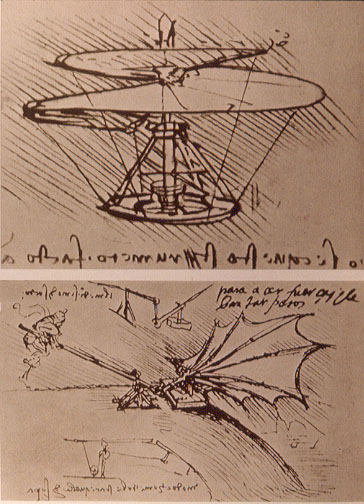

Da Vinci’s writings reveal an obsession with flight. After studying the complex motion of a bird’s wing, he devised a flying machine with bat-like wings that would be flapped by a person. A toy would inspire a kind of helicopter, utilizing a helical screw. Though basically thought experiments, the images display just how much of a visionary he was.

Helicopter and Lifting Wing, c. 1480s-1490s, credit Wikimedia Commons

Another of da Vinci’s obsessions was the human body, as a grandly complex machine. His study of anatomy probably took place from an early age. It wasn’t frowned upon at that time for artists in Florence to either perform dissections or watch them.

In often fetid conditions, Leonardo da Vinci studied the dead, and his way of presenting human body parts in cross-section and diagram very much informed the way they are seen in modern-day medical literature.

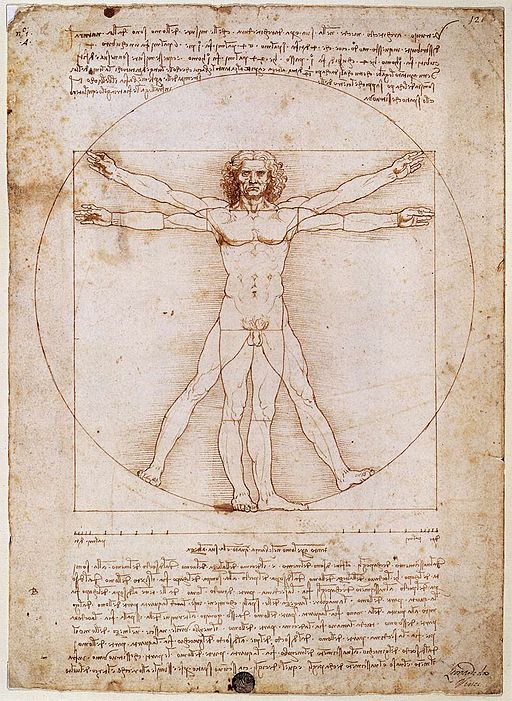

An especially notable piece among Leonardo da Vinci artworks is a drawing depicting the human body, known as “Vitruvian Man.” It depicts da Vinci’s conception of the ideal proportions of the human form. The nude body is shown in two positions, and is surrounded by a circle and a square. “Vitruvian Man” sits firmly at the intersection of science and art, just like da Vinci himself.

Vitruvian Man” by Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1492, credit Wikimedia Commons

In 1517, da Vinci went on to live in the court of King Francis I of France, a huge fan of the artist. As Favorite Painter Engineer and Architect, he wasn’t given anything to do, and so just sat back and enjoyed life. Leonardo da Vinci died there in 1519, at the age of 67.

Are you feeling inspired after reading this blog? Are you ready to create something extraordinary? Make sure to shop set below for your creation.