Table of Contents:

- The Origin of Abstract Art

- What is Abstract Art?

- Abstract Art at a Glance

- Abstract Artists and their Works

The Origin of Abstract Art

It could be said that abstract art has always existed in the world of artmaking. Art that is not a direct representation of the real world can be seen all the way back to prehistoric cave art. But it wouldn’t be until the 19th century that it coalesced into a modern art movement.

Theosophy was the primary influence on the first abstract artists. This religion was founded in 1875, and took parts of eastern religious thought, and science to create a movement centered on the evolution of the soul, symbolized in color and shape.

Consensus is that Swedish artist/mystic/theosophist Hilma Af Klint was the very first modern abstract artist, producing such works at the turn of the 20th century. Her theosophy practice led to attempts at spiritual artistic influence through seances. To Klint, though, these soulful expressions were not abstract paintings, just depictions of theosophical principles.

Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky is also considered a crucial pioneer and theorist in abstract art. He put abstraction on the map with his uber-influential treatise “Concerning the Spiritual in Art,” published in 1911. In this required read, Kandinsky calls for nothing short of a spiritual revolution in painting. He urges artists to look within for inspiration, and also states that the basic elements of a composition—color, shape, and line—can affect the soul in different ways. Kandinsky asserted that abstract art does depict reality, just a higher form of it that is obscured by traditional art.

In 1915, Russian abstractionist Kazimir Malevich unveiled “The Black Square,” a painting of a black square on a white field, and changed the art world forever. It could be, as Tate gallery puts it, “the first time someone made a painting that wasn’t of something.” Malevich explained that the black square equals feeling, and the white field around it equals the “void”—beyond feeling.

What is Abstract Art?

So, we have the basic artwork compositional elements—color, shape, and line that abstract artists work with. Two main ways to use these elements is either taking a real-world subject, and altering it, or rejecting the real world altogether. However, the definition of “the real world” is not as straightforward as one might think. For example, emotion is part of the real world, but not in the same way as, say, an apple.

The viewer’s gaze can be as important as the abstract art itself. Comprehension can shift depending on who the viewer is, where it is being displayed, and the point in time of the viewing.

Cubism is considered the first abstract art movement, and is seen as the most important art movement of the 20th century. The name came from art luminary Paul Cézanne, referring to “great classicist landscapes” having houses “like cubes.” This movement would flourish at the end of the first decade of the 1900s, and end at the start of World War I in 1914.

At the start, cubism split into two branches—analytical cubism and synthetic cubism. Both featured natural forms “analyzed,” disassembled and reassembled into two-dimensional geometry, and multiple perspectives were presented at once. For the analytic variety, form took precedence over color variety, and for the synthetic variety, there was far more color, and the works often contained collage elements.

Though there was a resurgence of abstract art after World War I, the run-up to World War II saw the center of abstraction move from Europe, to the United States. Many European abstractionists fled to the New World as the war raged, and brought their ideas with them. The stage was set for post-war abstract expressionism (abex).

Abex influences go all the way back to ancient myths and cultures, all the way up to the 20th century worlds of Jungian psychology and jazz music. They sought to instill strong emotional response in the viewer, using a mostly improvisational process. The process of creating the art held much of the meaning for many abex works.

Up to the present day the tenets of abstract art have been explored and re-defined in countless ways by countless artists, and it doesn’t show any signs of vanishing.

Abstract Art at a Glance

Here are some troubleshooting tips when attempting to understand abstract art:

- It’s not recognizable: So, you cannot make heads or tails of what a particular piece of abstract art is trying to say. A little research can go a long way—maybe seek out docents, literature, gallery talks, or even the label next to the piece.

- But my kid could do that: It may be true that some abstract art seems like it could be made by a doodling child, but the important distinction is intent. With the painting on display, there’s a deeper meaning at work. Also, elements that look “simple” may have involved a painstaking process to create.

- It’s too much to take in: A particular work may become easier to handle by distilling it into the basics of color, shape, and line, and taking it one compositional element at a time, then look at the whole.

Abstract Artists and their Works

Pablo Picasso: A 20th century art world giant, and pioneer of cubism. He pointed the way with 1907’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.” The oil piece is centered on five female nudes, flattened and angled, with facial features that hearken back to ancient Egypt, or appear to be African masks.

Mougins, France - 1966: Pablo Picasso standing by a green fern with folded arms, wearing a cashmere sweater. (Photo by Tony Vaccaro / Getty Images)

“Girl with a Mandolin” (1910) is a characteristic example of his analytical cubism. The color palette is limited, and after his cubist fragmentation and reassembling of the titular girl and mandolin, only the mandolin is recognizable. “Three Musicians” (1921) is a well-known example of synthetic cubism, which featured a cubist-rendered, multi-hued clarinetist, guitarist, and vocalist.

Picasso’s cubist works would mark the last time he played a part in revolutionizing the world of painting, but he wasn’t done producing art. It would be 1937’s “Guernica” that would become the most profound latter-day Picasso work. The namesake Basque town had just been bombed, and Picasso was deeply affected. He was inspired to create one of history’s greatest anti-war statements. The resulting monochromatic mural was an anguished tangle of panicked and wounded humans and animals. Here, he united the subconscious gestures of surrealism, and the unique geometry of cubism.

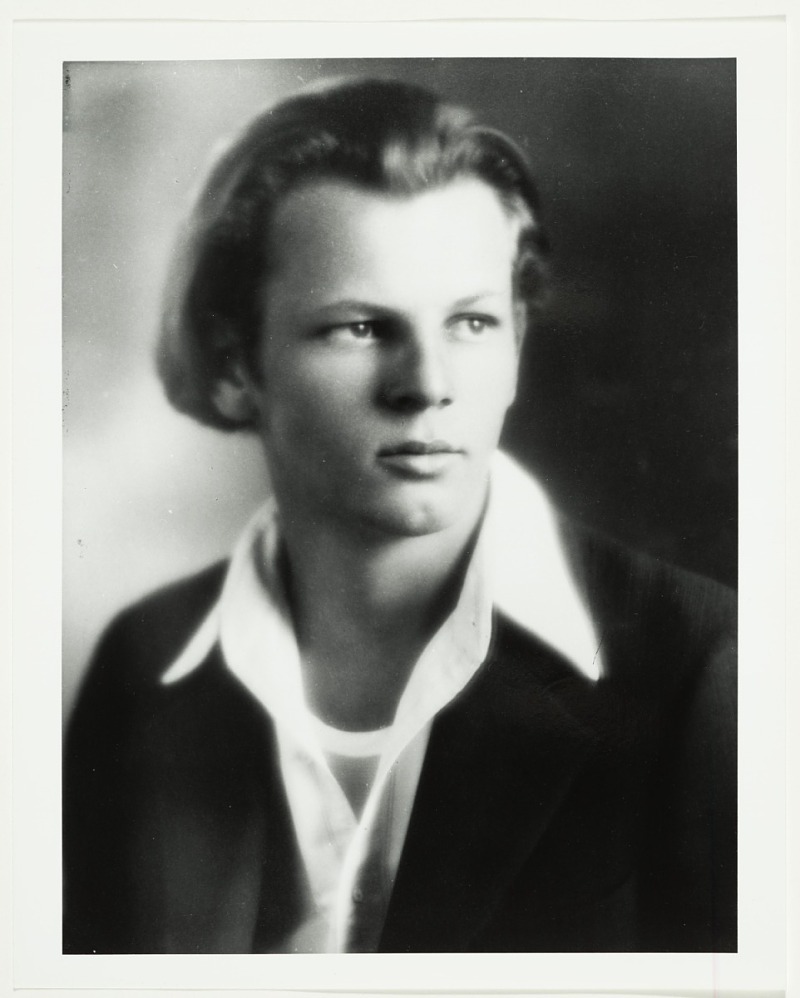

Jackson Pollock: Some thought he was a genius, others, a nut. As he became more and more known in 1940s New York art circles, Pollock’s works became more and more non-representative. On the heels of his first solo show, a commission by famed art patron Peggy Guggenheim resulted in a massive 19-foot-long canvas, dubbed “Mural.” It is a Pollock tour-de-force, with colors swirling across the expansive canvas and a repeated black stroke motif creates upright forms.

Jackson Pollock, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1947, Pollock commenced his most significant period of artmaking, laying a canvas onto his studio floor and using a “drip technique.” Pollock dripped, poured, flung, and scattered a variety of artist oils, enamel house paints and aluminum radiator paints using sticks, trowels, and palette knives. Pollock was aware of how his paint was flowing, how color was placed, and what to cover or leave exposed. He also knew what textures and effects would be produced by certain motions, artist tools, and paints. “Full Fathom Five” (1947) is a good example of all these elements at play.

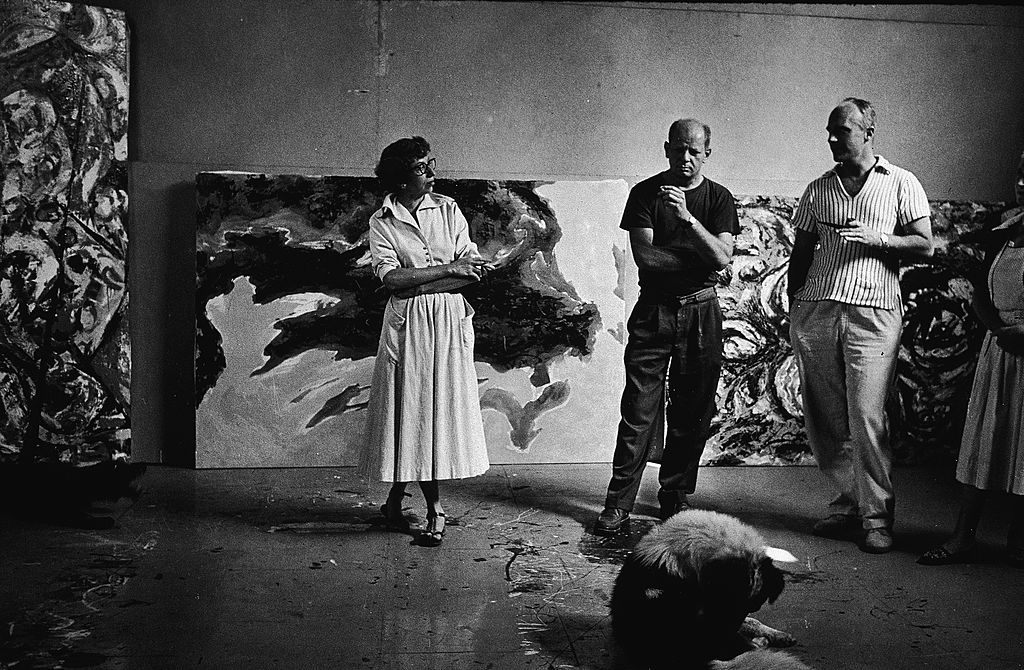

Lee Krasner: Her reputation as the “long-suffering wife” of Jackson Pollock is completely unfounded—she was a talented abex artist in her own right. She married Pollock in 1945, and the pair moved to a rural property in East Hampton, Long Island, New York, and each carved out a spot for a studio.

American abstract expressionist painter Jackson Pollock (1912 - 1956) (2nd left) and his wife Lee Krasner (1908 - 1984) (left) and an unidentified couple stand around a dog and smoke in his studio at 'The Springs,' East Hampton, New York, August 23, 1953. (Photo by Tony Vaccaro/Getty Images)

She adapted to her limited studio space with the “Little Images” series, produced from the late 1940s into the 1950s. They were created with thick paint, palette knives, and thick brushes, and have pronounced surface texture. As she discovered her own artistic voice, Krasner’s colors would brighten and the works began to take on a pointillist form. A grid structure would show itself more, as would geometric patterns and hieroglyph-like symbols.

Collage was also an important part of Krasner’s oeuvre. “Bird Talk” (1955) is a prime example, executed with oil, paper, photographs and collage on canvas, creating a kinetic, animated form in a kaleidoscope of colors with a black background. The work also alludes to nature, one of Krasner’s favorite themes.

Art and life were inseparable for Krasner, so whatever she was enduring would end up on the canvas. One especially fraught moment was around the time Pollock died. She was working on a painting series inspired by both Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” and Pollock’s drinking problem and infidelity.

Willem de Kooning: De Kooning was a fuser of styles—his abex influence can be seen in his assertive and gestural manner, along with conventions of cubism and surrealism. But, according to the man himself, space and figure-ground relation were the actual subjects of his paintings.

The painter Willem de Kooning (1904 - 1997) closely examines the surface of one of his abstract paintings, in his studio, Long Island, New York, 1967. (Photo by Robert R. McElroy/Getty Images)

De Kooning would garner notoriety with his depictions of females, most exemplified by his famed “Women” series, first shown to the world in the early ‘50s. “Woman III” conveys the sensibilities of this body of work. Amid the colorful, energetic gestural strokes is the form of a voluptuous woman, blond and smiling. The figure’s tapering calls to mind ancient idols. In what will become a de Kooning trademark, background and foreground are hard to tell apart, something the artist called “no-environment.”

In the wake of his newfound fame, de Kooning pivoted to landscape painting. “Rosy-Fingered Dawn at Louse Point” (1963) sees bold strokes in abstract pinks, yellows, and blues floating on the canvas like pastels. De Kooning’s paint texture varies from thin to impasto.

Franz Kline: Originally inspired by Old Masters, Kline moved to large-scale abstraction in the late ‘40s, upon viewing pioneering abex efforts. To that end, he worked with a largely black-and-white palette, using house painting brushes to deploy strokes of black paint onto white canvases. In true “action painting” style, Kline moved his whole physical self to assertively apply pigment onto canvas.

A picture (untitled) by US American painter Franz Kline (1957) can be seen at the Hamburger Bahnhof contemporary art museum in Berlin, Germany, 05 June 2015. The piece is part of the exhibition 'Black Mountain. An Interdisciplinary Experiment' 1933 - 1957. Photo by Stephanie Pilick, Getty Images

An untitled 1957 piece, which sold for $40.4 million at auction in 2012—a record for a Kline work—is a characteristic example of prime Kline. Black pigment flies across the canvas in thick trajectories as a statement of power and energy.

Helen Frankenthaler: In a world of somber artists, Frankenthaler was happily enthusiastic, playful, and adventurous. She was an abex artist who lived in and was inspired by the beach house atmosphere of Provincetown, a town located at the tip of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. She called her genre “Abstract Climates.” This atmosphere is unmistakable in “Beach” (1950), for example. Here, she combines paint, plaster of Paris, coffee grounds, and sand to place the viewer directly into her world.

American abstract expressionist painter Helen Frankenthaler in her studio, New York, New York, 1978. Photo by Brownie Harris/Corbis via Getty Images

Frankenthaler developed a Pollock technique variant she called “Soak-Stain”—spilling and pouring oil paint that was rendered near-watery in consistency by turpentine and kerosene. This was used in her beloved, landmark work, 1952’s “Mountains and Sea.” This oil and charcoal on canvas has been called the “Rosetta Stone” of the color field movement. “Color field” is a branch of abex that has color take center stage in flat, solid expanses across the canvas.

The great thing about abstract art is the plethora of ways it can be explored, using a wide array of art-making tools. Though critics may have scoffed at abstract art, don’t listen to them—have fun and go wild on that canvas!

If after reading this blog post you feel inspired to create, make sure to view our Arteza trending now products below and stock up on your favorites!