Table of Contents:

The Road to Art Deco

A painting hangs on a wall. A sculpture sits on a base. Much of visual art just exists in a space in an aesthetically-pleasing way. But not art deco. For this emphatically modern movement, artworks tended to serve a purpose, in addition to being artistic.

To find out about the origins of the art deco style, we must go to France at the close of the 19th century. Up to this point, the art world was dominated by classical painting and sculpture produced by formally trained artists. But as the modern world coalesced, the decorative arts gained significance among French artists. This genre was historically ranked below classical art, and included ceramics, glassware, jewelry, furniture, textiles, clothing, as well as such graphic arts as fashion illustrations, posters, book covers, catalogs, and playbills.

Art nouveau was the first movement in which the decorative arts took off. The origin point of this movement was in 1890, when a group of French artists, architects and designers began creating works that emphasized hand-crafted natural forms, extensive detail, delicacy, and expensive materials.

As the first decade of the 20th century dawned, art nouveau practitioners formed the Society of Decorative Artists, and the group planned to put on an exhibition in 1914 in Paris, but World War I caused it to be postponed. However, during the span of the war, art nouveau became passé, as its aesthetic seemed out of touch with the increasingly technologically-advanced world.

By the time the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts finally took place in 1925 (known as the “Paris 1925 exhibition” for short), art nouveau was out and art deco was in.

What is Art Deco?

The world became aware of art deco at the Paris 1925 exhibition, which hosted more than 15,000 artists, architects, and designers who displayed their works, and it was visited by more than 16 million people. The actual name “art deco” derived from the name of this exhibition, but the movement didn’t have this official moniker until the end of the 1960s.

Art deco arrived in America via U.S. manufacturing delegations who attended the 1925 exhibition, and the style made a huge splash. Its arrival brought about a change in how art was displayed. Since art deco items had actual functions, it made sense for department stores, such as Lord & Taylor in New York, to take the place of art galleries and museums. They would even commission less-costly U.S. versions of expensive European creations.

The art deco style embraced new technologies, just-invented modern materials, and mechanization, which brought it to millions of Americans. Machines allowed for mass production, and the simple geometry made designs easy to reproduce. For art deco artists, if a machine can make it, it shouldn’t be handmade, and materials should look like themselves.

Everything from food and cosmetic packaging to electronics sported art deco’s zigzags, sunbursts, lightning bolts, chevrons, bold patterns, and color contrasts. Even Egyptian motifs showed up, right after King Tut’s tomb was discovered in 1922.

Streamlining was huge in art deco, reflecting man’s ability to travel at unprecedented speeds. The “windblown” style became omnipresent and often unnecessary. After all, a vacuum cleaner does not have to have the same lines as a race car to function properly.

Artists working in art deco had an array of new materials to work from. Stronger structural glass allowed it to be load-bearing in architecture and furniture. Bakelite, the first synthetic plastic, was used in all manner of electronic gadgets, ideal because it is electrically non-conductive, and resistant to heat. It could also be molded into any shape and made into any color. Polished molds made the products “shine.”

Escapism was a major part of the art deco era, a desire spawned from war and economic hardship. One of the major ways millions of average Americans escaped was through a trip to the movies, where they would be exposed to a ton of art deco motifs. The quality of filmmaking and the film stock itself was improving, so audiences could better appreciate the increasingly elaborate, art deco-inspired sets. In fact, there was a “golden age” of set design and fabrication in Hollywood, when studios hired on some truly talented artists.

World War II brought an end to art deco as a movement, but the style hasn’t gone anywhere, and remains one of the 20th century’s most distinctive art forms.

Art Deco at a Glance

Art deco was unlike many well-known art movements. Here’s some unique aspects:

- There’s more than one: Art deco works, especially household items, tended to be mass-manufactured, not be one-of-a-kind.

- It serves a purpose: An art deco piece does not just sit there; it can be used. For example, a vacuum can be a striking art deco piece, but still function as a vacuum cleaner.

- It’s made of modern materials: Scientific innovation enabled art deco works to be made of such innovative materials as synthetic plastic and structural glass.

- It’s for everybody: In many cases the wealthy were not the only ones who could afford art deco products.

Art Deco Artists and their Works

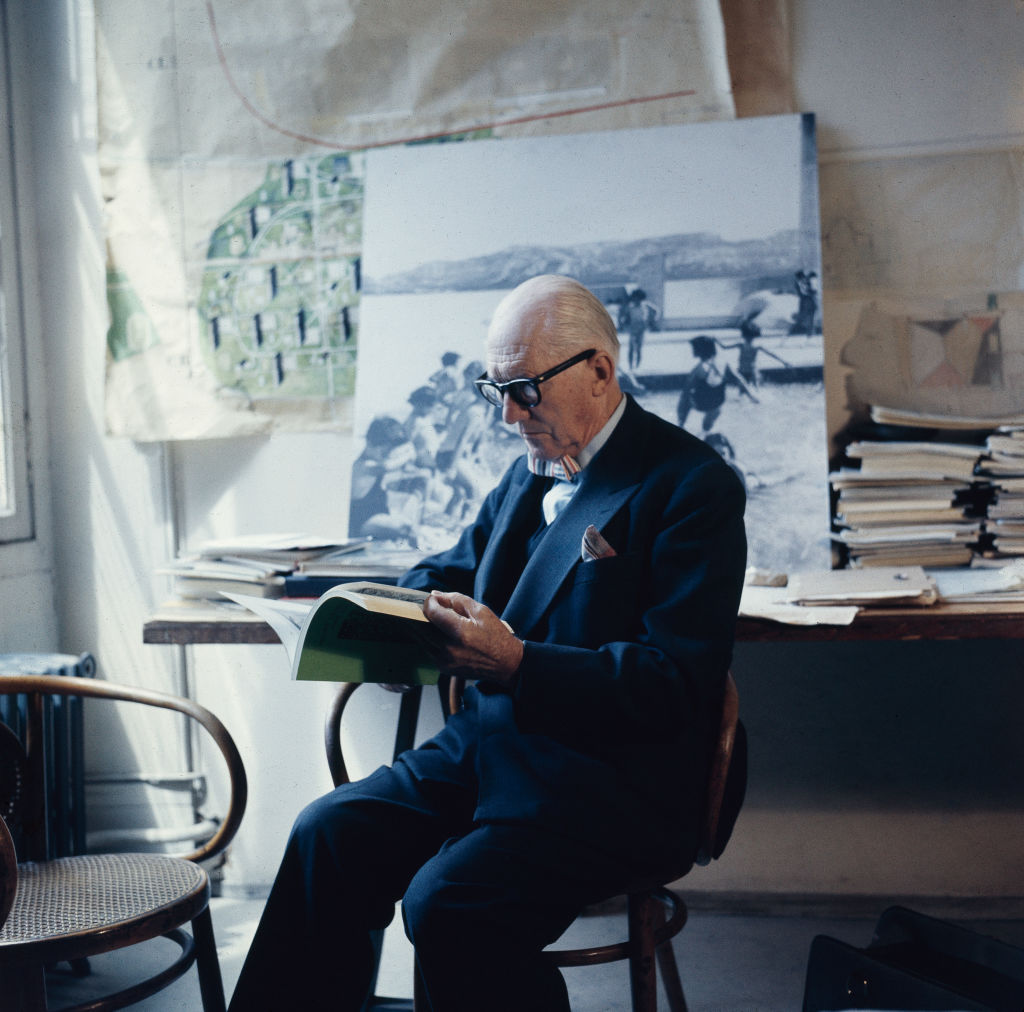

French architect and painter Le Corbusier at his studio, France 1960s. Photo by Wolfgang Kuhn/United Archives via Getty Images

Le Corbusier: This Swiss architect, who had his own pavilion at the 1925 Paris show, played a key role in conceiving modern architecture. He felt that engineers and architects were at the same level as visual artists. He pared-down his art deco creations to such a degree that he has been called “anti-decorative.” They were the very image of modern cleanliness, efficiency, and neatness.

When Le Corbusier designed a house, he had only core essentials in mind: shelter from outside elements, a place for light and sun to enter, and rooms, which he called “cells,” wherein one can cook, work, and have a personal life. He envisioned giant apartment buildings containing tens of thousands of residents. Le Corbusier controversially advocated for the demolition of all buildings from the past and starting from scratch, creating an expansive urban design masterpiece.

In the 1920s and ‘30s, Le Corbusier did design homes and erect apartment buildings in the Paris area, but his super-stark designs look dreary to many. In the end, beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

Tamara de Lempicka: One of the only creators of art deco paintings, which, while they didn’t combine form and functions, are still revered as masterworks. Fleeing the Russian Revolution in 1917, de Lempicka went to Paris and on to become an independent, successful artist. She fit right in with the talented and hedonistic Parisian avant-garde.

Tamara de Lempicka at Her Easel, Getty Images

De Lempicka was inspired by the emerging Roaring 20s “new woman” trend, the name given to the era’s confident and independent women. Her figures and backgrounds contain bright hues, plus angles that subtly draw from cubism. Her works are futuristic, super-precise, and almost robotic.

Up until the mid-30s, de Lempicka’s art deco works were populated by often-unclad voluptuous women relaxing in private and out in urban environs. A prime example is 1923’s “Perspective” oil on canvas, which features two basking female nudes.

She also gained notice for her oil-on-panel self-portrait “Autoportrait (Tamara in a Green Bugatti)” (1929), which was created for the cover of the German lifestyle magazine “Die Dame.” It is the embodiment of her social position as a modern woman of means. In the work, de Lempicka is in the driver’s seat, looking right at the viewer with coolness in her eyes, silk scarf caught in the wind, gloved hand on the wheel.

De Lempicka garnered critical acclaim, awards, spots in Parisian galleries, exhibitions, international fairs, and commissions to paint portraits of the rich, celebrities and royalty.

She became famous and wealthy, and lived a glamorous life. However, she remained a savvy businesswoman who understood the importance of self-promotion.

Erté: Due to his efforts in art, fashion, and set design, he earned the nickname “The Father of Art Deco.” His birth name was Romain de Tirtoff, and he came from an aristocratic Russian family. When he defied their wishes by going to Paris in 1912 to study design, he concealed his lineage by coming up with the alias “Erté,” the French pronunciation of his initials “R” and “T.”

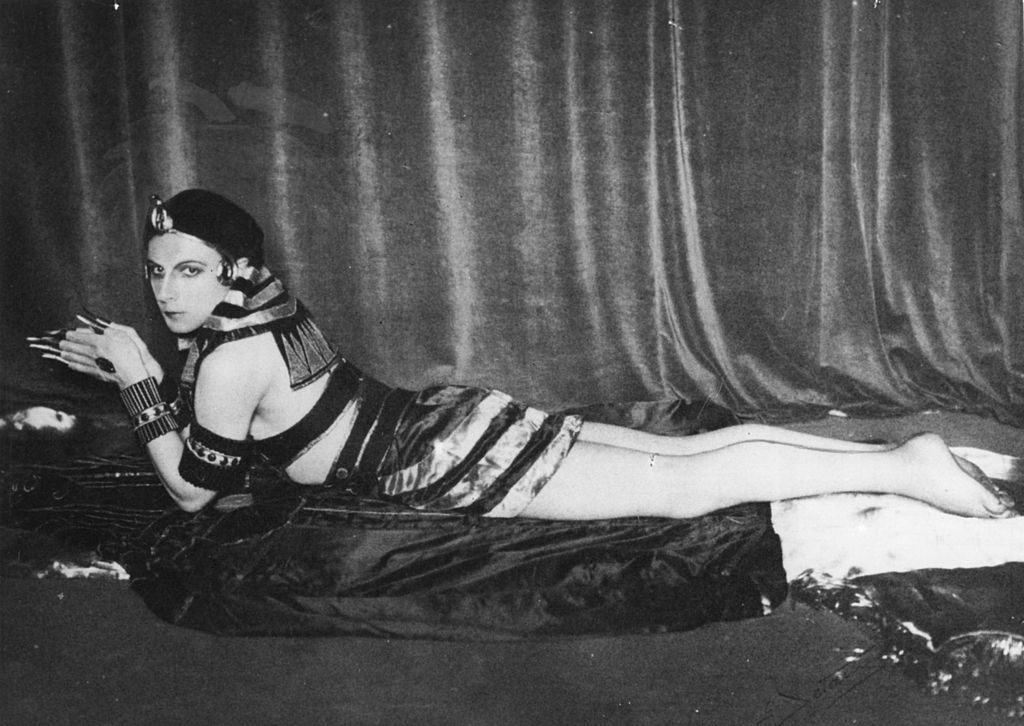

Erté In Costume, Artist and designer Erté (Romain de Tirtoff, 1892-1990) poses wearing an Erte-designed costume, 1929. Photo by Evening Standard/Getty Images

It would be fashion magazine covers that truly put Erté on the map. In 1915, he created his first of more than 200 covers for pioneering fashion publication “Harper’s Bazaar.” “Cosmopolitan” and “Vogue” also published his work. These art deco fashion illustrations pulsed with sophistication, romanticism, extravagance, exoticism, and style.

Erté’s roster of clothing design clients was filled with notables, like notorious dancer/spy Mata Hari, as well as actors Sarah Bernhardt, Josephine Baker, Joan Crawford, Lillian Gish, and many, many more.

The artist eventually designed costumes and sets for Hollywood movies beginning in 1925. His first foray into movies was the silent film “Paris,” and later, you could see his work in “Ben-Hur,” “The Mystic,” and “Dance Madness.”

Georges Lepape: Being born in Paris towards the end of the 19th century meant that the city’s art scene was right at his doorstep. He was a pioneer in the melding of fashion and visual art in the art deco style.

“Vanity Fair” cover by Georges Lepape. Cover from December 1919. Gouache over pencil on bristol board, 34.9 x 26.8 cm. Photo by VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images

Lepape got his start as an illustrator for Paul Poiret, a pioneering giant in the high fashion world. His illustration work would eventually grace book covers, posters, and catalogs.

But it was be his role as a fashion illustrator for “Vogue” and other notable fashion publications in the 1920s that caused his reputation to skyrocket. Until the mid-1930s, he would be considered “Vogue”’s most brilliant artist.

Lepape’s major influences ranged from orientalism to Persian miniature paintings, and the look of the popular ballet group Ballets Russes. He also had a recognizable curvilinear style. Lepape introduced some innovations to art deco fashion illustration, including a sense of motion and story, depicted through the thin, turban-bedecked female figures departing from the frame, and facing away from the viewer. His illustrated ladies were unmistakably confident, independent, modern, and witty.

René Lalique: Before becoming an art deco luminary, Lalique was an art nouveau master. By 1900, Lalique had reached the highest echelon of jewelry-making in France. However, by 1903, he grew weary of constantly being copied, and shifted to glassware. Lalique designed incredibly ornate perfume bottles and stoppers for top perfume designer François Coty.

People look at perfume bottles made by René Lalique ("Dans la nuit" and "Je reviens"), in April 1947 during a visit to the Worth perfume workshop in Suresnes. Photo by - / AFP) (Photo by -/AFP via Getty Images

Lalique’s use of glass produced some of his most notable works. Glass making is a very complex process which takes skill and an incredibly hot furnace. Depending on the mix of chemicals, opacity and color can be manipulated, and Lalique also experimented with dichroic glass, which, depending on the lighting can shift between two completely different colors. Lalique also used a lost wax method when casting glass, which made for easy duplication of a design.

Lalique was another artist present at the 1925 Paris exhibition, and he even designed a giant glass fountain for the occasion. He dove right into the art deco style, with spectacular results.

In 1928, Lalique commemorated the 10th anniversary of the WW I armistice with the “Victoire,” or “The Spirit of the Wind” piece. It is an art deco glass hood ornament bust definitely showing speed even when standing still, its hair streaming backwards. After glass stopped being used in hood ornaments, Lalique adapted the design into bookends and paper weights.

The results of Lalique’s decorative efforts on the SS Normandie could be considered his magnum opus. The ship was a giant, opulent ocean liner launched in 1935, and dubbed the “Floating Temple of Art Deco.” The ship’s first-class dining hall would be Lalique’s canvas. This room was already the largest single space at sea at the time, at 305 feet long, 46 feet wide and 28 feet high.

Lalique brought illumination to the room, which could not admit natural light. He installed 12 tall pillars of glass and along the walls, 38 matching columns, plus chandeliers at each end of the space. They were a tour-de-force of simple, yet strikingly modernist geometry plus subtle Grecian elements.

You don’t need a glassworks or an entire building to dive into the art deco style. Its distinctive streamlined geometry can easily be explored with drawing utensils, a piece of paper, and some photos of iconic art deco works for inspiration. Go ahead, see what you can come up with!

After reading this blog post are you motivated to create some art? Make sure to shop the suggested set below for your next creation