Table of Contents:

It hasn’t always been smooth sailing in the United States of America, as 2020 has taught us. Political, ideological, and social divisions are especially wide nowadays, and the COVID-19 pandemic experience has been an unmitigated hurdle for our country. As we celebrate Lincoln's birthday today, as well as the approaching Presidents’ Day—we are reminded of another time of national division—the Civil War. The United States split in two over the issue of slavery, and hundreds of thousands of Union and Confederate soldiers clashed.

From the 1700s to the mid-1800s, America’s leaders struggled with the concept of slavery—abolitionists condemned it, but it was big business, making a lot of plantation owners very rich. The U.S. government employed a series of compromises and laws as the nation expanded until compromise became impossible. Though the Union won the Civil War and slavery was abolished, the total Civil War death toll is staggering. Estimates range from 680,000 to 800,000—more than the American Revolution, World War I, World War II, and the Vietnam War combined.

And the guiding light of the Union through it all was Lincoln, the Great Emancipator, who kept the Union together, and played a key role in ending slavery within the U.S. borders; which began with the Emancipation Proclamation and was set in stone by the 13th Amendment.

Civil War art depicted the conflict in a variety of mediums for the average Americans to witness in action. Here, we will examine war art in photography and illustrated newspapers, and in the spirit of Black History Month, discuss notable African American artists of the period.

Civil War Photography

The Battle of Antietam took place on September 17, 1862, near the town of Sharpsburg, Maryland. The Union won the battle, but it was the costliest single day in the entire war, with 22,717 dead, wounded, or missing. Just days later, an enterprising photographer named Mathew Brady opened an exhibition of photographs in his New York City studio called “The Dead of Antietam.” The images, taken by Brady team member Alexander Gardner, unflinchingly depicted the aftermath of the battle. These grim images shocked the public and eliminated notions about the romance of war.

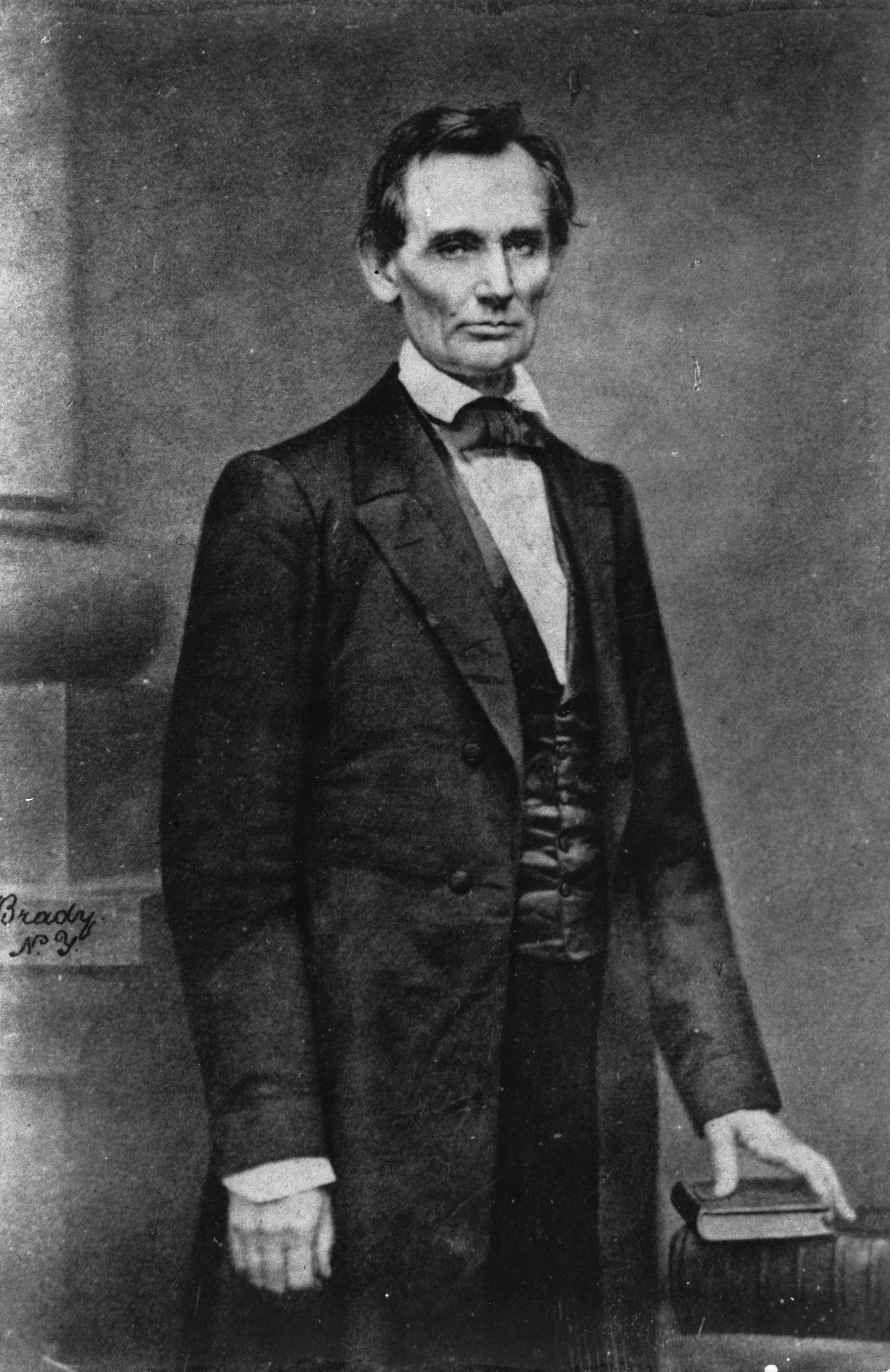

Brady has been called the “Father of Photojournalism” and he considered photography to be an artistic expression, not dissimilar to paintings of war. He took to the medium as a young man, and by the 1850s, he had opened an additional studio in Washington D.C. Here, while considered to be one of America’s top photographers, he was snapping portraits of some of the day’s most notable political personages, and foreign dignitaries, and was the favored photographer of Abraham Lincoln. In fact, it was Lincoln himself who gave permission to Brady and company to formally photograph the war.

"Abraham Lincoln" by Mathew Brady, Wikimedia Commons

It should be noted that Brady didn’t create all of the war art attributed to him. He is seen now as a “project manager” of sorts—overseeing his photographers and tending to the negatives.

"Battle of Antietam", 1862, Wikimedia Commons

The Civil War would be the first armed conflict to be extensively documented by photography. Life in troop encampments, battle preparations, the pained faces of the wounded, the dead sprawled on the battlefield, grim-faced soldiers of every rank, southern cities in ruins—the photographers captured it all.

But creating this Civil War art was not easy. The danger of battle, dust, and mud was ever-present. The portable darkroom, dubbed the “What is it?" wagon by soldiers, contained delicate glass plates, and a witch’s brew of deadly, expensive chemicals. Camera equipment was bulky, so it could withstand the rigors of travel.

The complex photographic process used is known as “wet-plate collodion.” Basically, a fixture called collodion is poured onto one side of a glass plate. While the plate was still tacky, it had to be handled in darkroom conditions, immersed in a bath of silver nitrate, then loaded into a plate-holder. Then the clock began ticking. You had just a few minutes to take the photo, before the coating dried and the plate became useless. The plate-holder was mounted into the back of the camera, and a slide was pulled back to get the plate ready for exposure. The lens cap was removed to expose the plate, and replaced once the photo was taken. The plate was fixed, washed, dried, and varnished.

A major innovation at the time allowed photographs to be printed on paper. By placing paper coated in albumen (basically chicken egg whites) over the glass negative in a vat of silver nitrate, a copy was created. These paper prints sold by the thousands, and enabled soldiers to exchange photos with loved ones, even by mail.

Different camera configurations allowed photographers to portray a person or scene in different ways, such as the “carte de visite” format, which created four identical photos, and “Stereographs,” which were produced using two lenses to take a photo that could be seen in 3D by using a special viewer much like a View-Master.

Illustrated Newspapers

But there was a shortcoming to the photographic techniques of the day—it was impossible to snap an image of battle as it happened. The only way the public could get a sense of the action during the war was through illustrated newspapers and magazines. Many famed Civil War battle paintings were created after the end of the war.

The modern conception of the professional war correspondent journalist came into being, and alongside that close-knit group of battle chasers nicknamed the “Bohemian Brigade,” were illustrators. The artists had to be quick and observant when creating this war art, even when close to the maelstrom. Sketches were sent back to the publication, where teams of draftsmen and engravers transformed the sketches into woodblock engravings, which allowed the images to be printed.

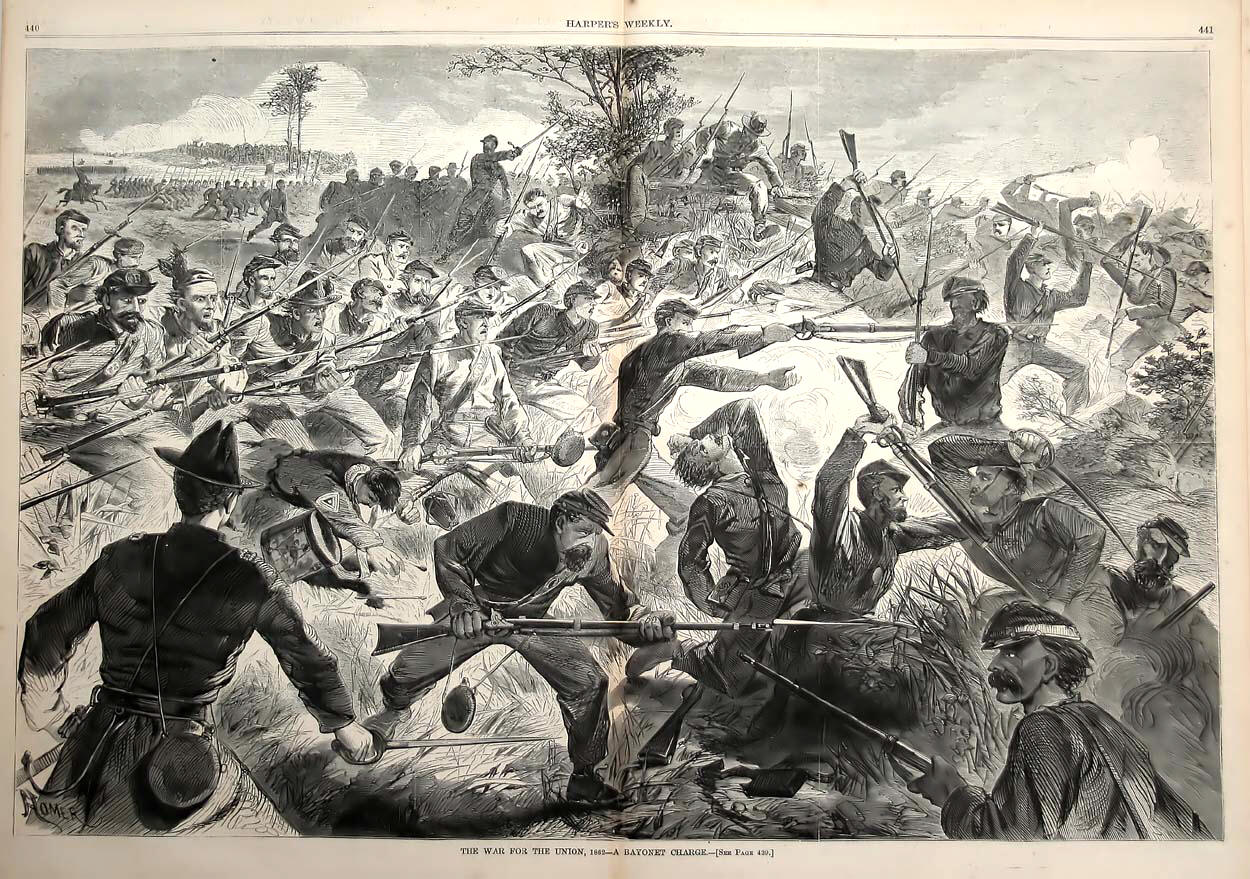

One of the most significant illustrated publications of the times was “Harper’s Weekly,” founded in New York in 1857. As the war progressed, “Harper’s” published hundreds of examples of this Civil War art, including Brady’s photographs rendered by the engravers. One acclaimed “Harper’s” artist who would become a legend was Winslow Homer. His skills were recognized even early on in his career as an illustrator. A quintessential Homer work was “The War for the Union, 1862 - A Bayonet Charge,” published July 12, 1862. The piece depicts combat at Battle of Seven Pines, aka, Battle of Fair Oaks, near Richmond VA.

"The War for the Union", 1862 - A Bayonet Charge, Wikimedia Commons

African Americans Artists

Despite the anguish and turmoil of their existence at the time, African American artists in the Civil War era were still able to produce stunning art.

Robert S. Duncanson was part of the Hudson River School, a now-famous group of American landscape painters based in New York City. His work was lauded by contemporaries and art historians, and he is recognized as one of the top African American artists of the period. Though in a kind of exile in Europe during the span of the war, he was still very conscious of what was happening in the U.S. during that time and returned soon after the war was over.

“Land of the Lotus Eaters,” painted in 1861 is a great example of his work, a languid tropical landscape inspired by a Tennyson poem about a seductive land in Homer’s “Odyssey.” But there’s more there than a tropical paradise, that makes it a Civil War painting. Look again at the bottom left—it’s a group of white men at leisure being served by dark-skinned individuals.

"Land of the Lotus Eaters", 1861, Wikimedia Commons

Edmonia Lewis became internationally renowned as a sculptor during the Civil War, blending her experience as both a black and Native American woman with a Neoclassical style. Her war art took on a metaphoric frame with “Forever Free” in 1867—the title is a direct quote from Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. The marble sculpture shows a woman kneeling in prayer and a man standing, holding a broken chain that is not restraining him. His hand is on her shoulder. Lewis was celebrating freedom with this sculpture, but, more complexly, she conveys the subordination of women and the lingering oppression of African Americans.

"Forever Free", 1867, Wikimedia Commons

Civil War art very much mirrors the war itself; a blending of old with new. For example, the military strategy of old met with new ways of waging war, and with art, composition principles that have been employed since ancient times were applied to the brand-new medium of photography. The old system of slavery was ended, and African Americans attained the newness of freedom.

2 comments

We thought so too, Mary!

Very interesting story of early photography and the roll it played in recording historical events!