Happy birthday to the ultimate vagabond artist, Paul Gauguin! It’s pretty amazing that this Frenchman acquired his status as a legend when he didn’t start painting until his mid-30s, and had no formal training.

Gauguin has a place among the most significant painters of the late 1800s, and his experiments with abstraction, color, and form would make Paul Gauguin’s art quite the inspiration for a number of famous modern artists who would come later, including Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse.

Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin entered a world in turmoil. He was born in Paris, France in 1848, the same year that Europe saw widespread revolution, and Gauguin had a personal connection to it. His father was a liberal journalist, and his grandmother was a writer, socialist society member and activist who played a part in instigating some of the unrest.

Then the French powers-that-be suppressed the newspaper that Paul Gauguin’s father wrote for, and the Gauguin family had to flee France. They headed for the South American country of Peru. Tragically, his father died during the trip, but the rest of the family survived the voyage. It would be the first of many Paul Gauguin cruises. Young Paul Gauguin lived in the lap of luxury while in Peru, a perk gained from being related to the country’s leader. After five years in Lima, civil war erupted, and the government fell from power. So, the Gauguin family was on the move again, and ended up back in France by the mid-1850s, where they lived a much more modest existence.

Gauguin later claimed to have Incan lineage (the ancient civilization that lived in what became Peru), and declared it as an incredibly formative aspect of his life. But that was just one of the many false personas that he habitually adopted.

Paul Gauguin, French painter born in Paris (France). Ca. 1885. Photo by adoc-photos/Corbis via Getty Images

Fast-forward to the 1880s, we reach the genesis of Paul Gauguin’s art pursuits. At this time, Gauguin was 35, married, had four kids, and was working as a stockbroker.

In 1886, he became intrigued by his mother’s collection of old Peruvian pottery, and was then inspired to take up the art form himself. Though painting got him much of his attention, he dabbled in sculpture all his life, and this early effort would be the first of many forays into ancient themes.

It would be his modern art collecting that truly got the ball rolling, directly leading to all those classic Paul Gauguin paintings. As he took in the bright and diffused in-the-moment impressionist paintings in his collection, he was inspired to start creating canvases in this style during his off-hours. He received encouragement from Camille Pissarro, a famed impressionist whose art he collected. Gauguin soon left his stockbroker job to paint full-time.

Paul Gauguin’s wanderlust and desire to escape the modern world grew strong, and starting in the mid-to-late 1880s, he was often on the move, visiting and revisiting favorite locales. And throughout his journeys, he would become an innovative voice in the art world.

First, he decamped to the diminutive village of Pont-Aven in Brittany, France, about 320 miles from Paris, leaving his wife and children behind. Here, the modern urban life in Paris was replaced by farming and fishing, unchanged from centuries before.

Fully immersed in his art, he played a part in pioneering the post-impressionist “symbolism” painting style. Simply put, with impressionism, a tree is a tree, as seen through the eyes of the painter. But with symbolism, it is more than just a tree. True, symbolists would paint trees, along with other typical painting forms, but what is truly being expressed ranges from the lightest to the darkest aspects of the human condition. Paul Gauguin paintings from this period reveal a pioneering color theory that is common to the symbolist style.

“The Yellow Christ,” an oil on canvas which Paul Gauguin created in 1889, is considered a key symbolist painting and is also a notable for its “cloisonnism” style—a depiction of bold and flat forms separated by dark contours that would become a prime characteristic of Paul Gauguin art moving forward. A crucifix from the 1600s that hung in Pont-Aven’s Trémalo Chapel inspired the work.

It’s not a garden variety Christ crucifixion scene, though. Christ is rendered in a conspicuously bright yellow tone, and instead of outer Jerusalem in the background, there is a bucolic scene of northern France in autumn. Gauguin said that this specific yellow hue represented his feelings related to the isolation and religiousness of the local peasants—some of whom knelt at the base of the cross, dressed in their distinct regional clothing, and engaged in their traditional evening prayers. The fact that “The Yellow Christ” depicts an autumn scene is no accident. For Brittany’s devout Catholics, the autumn harvest has deep meaning. They saw the grain’s life cycle as analogous to the Christian’s life: born, living, dying, and being reborn.

In 1887, Paul Gauguin’s cruise to the Central American country of Panama in a bid to restore his energy. He only stayed a few weeks, departing for the Caribbean island of Martinique after enduring both malaria and dysentery. Martinique was more artistically stimulating, and Gauguin embraced the tropical scenery and people. Back in France by the end of the year, he returned to Brittany, favoring the less-touristed fishing village of Le Pouldu.

He become a lead voice in “synthetism” while in Le Pouldu. This post-impressionist style sought to synthesize forms in nature, how he artist felt about the subject, plus pure line, color, and form. “Vision after the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling with the Angel),” a synthetism work created in 1888, became one of those famed Paul Gauguin paintings. There are two main elements to the composition, a group of praying women wearing the typical rural Breton garb: stark black outfits with yellow-white bonnets; to their right is a rendering of Jacob wrestling an angel, an incident referenced in the Bible’s “Book of Genesis,” which was the subject of the sermon the women had just heard. The background is a striking shade of vermilion. Gauguin was proud of how the figures exuded the simple, rural, and superstitious. The Breton women are, in fact, not witnessing the wrestling match in person, it is happening in their imaginations—a characteristic departure from the real for this modern art style.

Around this time, Gauguin had his fabled visit with Vincent van Gogh in Arles, France. It was an interpersonally stormy stay, and, in fact, he was in town when van Gogh severed his own ear.

Soon after, Paul Gauguin’s life changed forever when he explored the myriad exhibits at the 1889 Exposition Universelle world’s fair in Paris. He came upon a depiction of life on Tahiti, one of the islands in French Polynesia in the South Pacific. Gauguin fell in love and immediately started making plans to visit. For him, it would be the ultimate escape from the modern into the natural.

Paul Gauguin cruised to this area birthed another major stylistic exploration for him: “primitivism.” He was a key mastermind in this artistic movement, which would profoundly influence European and American painting. Gauguin melded real-world South Pacific sights with symbols of the mystical, and was inspired by often-ancient primitive art. He portrayed a deep connection between nature and one’s fellow humans, and explored profound ideas related to the meaning of life and nature, as well as the essence of religion—things that come to the fore when modern life is absent.

Paul Gauguin was drawn to the 19th century European concept of the “noble savage,” an archetype that the artist saw as in opposition to the era’s widespread greediness, corruption, and destitution.

It was in opposition to the so-called “brutal savage,” often-violent peoples that European colonizers were encountering. The “noble savage,” though uncivilized, was free of the corruption brought on by modern life, and so possessed innate goodness. It was an idealized, yet vastly over-simplified view of these peoples.

Tahiti was not all it was cracked up to be at first. Gauguin arrived at the capital of Papeete in 1891 expecting paradise, but encountered a French colony plagued with disease, and occupied by government officials and missionaries.

Despite this, Paul Gauguin’s paintings embody the ideal vision of Tahiti, and he wouldn’t abandon his desire to find that idealized place for real.

Paul Gauguin, “NAFEA Faa Ipoipo” (“When Will You Marry?”), 1892, credit Wikimedia Commons

“NAFEA Faa Ipoipo” (“When will you Marry?”) (1892) presents both sides of the Tahitian divide. The composition is dominated by two women, a younger, alluring one in traditional Tahitian dress, and an older almost mother-figure in western dress. There is a flower adorning the younger one’s hair behind the ear, indicating her availability for matrimony. But not all is well. The young woman seems to be nervously glancing to the side, and figures walking up from behind them may not be completely welcomed into the moment shared by the two women. This juxtaposition of paradise and potential trouble reflects reality—Tahiti’s departure from Eden-like paradise.

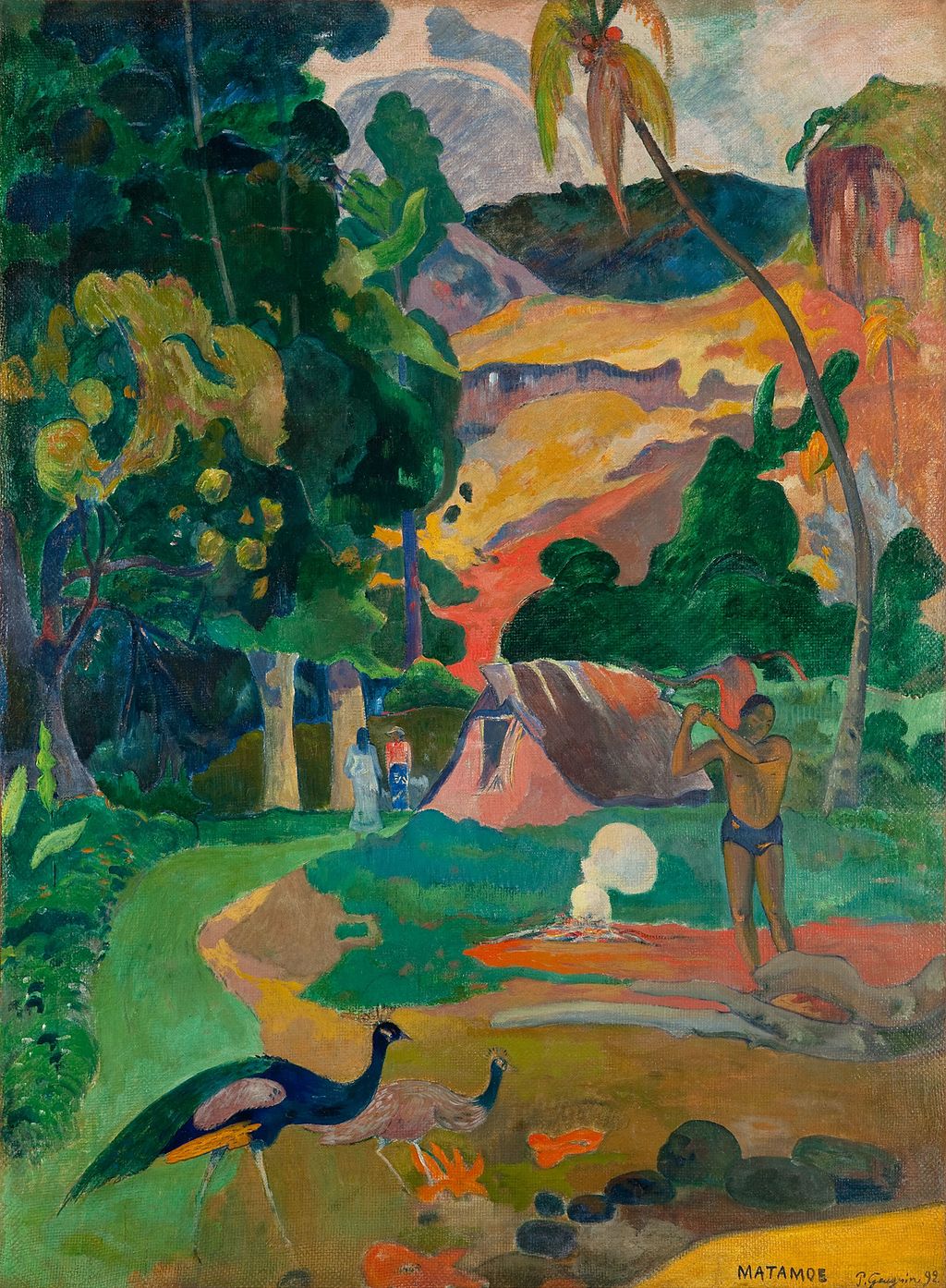

Paul Gauguin, “Matamoe (Death), Landscape with Peacocks,” 1892, credit Wikimedia Commons

“Matamoe” or “Landscape with Peacocks” (1892) is an unabashed affectionate tribute to the beauty of Tahiti, and is among the most celebrated of Paul Gauguin paintings. “Matamoe” is Tahitian for “death,” and experts discern that this is a reference to Gauguin being “reborn” after arriving on the island. It is a carefully constructed image of a clearing in thick tropical jungle with uplands in the distance. The clearing contains a hut and in front of that, a young islander raises an axe, about to cut down a coconut tree. Beside him a small fire is burning, then in the closest foreground, two peacocks stroll by. His use of color is stunningly vivid, and almost psychedelic.

It should be noted that Paul Gauguin’s art was rife with fabrication and blending of cultural symbols. He wasn’t able to find much information about Tahitian mythology, so he made up names and depictions of deities. Tahitian imagery could take on tones of Egyptian art or Christian iconography. This can be seen as culturally insensitive, but a familiar element in modern art at this time was to see the common spirit behind all things, so Gauguin may not have seen any difference between these cultures, in the end.

Eventually, Paul Gauguin returns to Paris, but after a few years without making a splash in the art world, he set out again for his beloved South Pacific. And in a refreshing turn of events, a stop-off in an Auckland, New Zealand museum resulted in some authentic insight into the history of the Tahitian people. As it turns out, New Zealand’s indigenous Maoris originally came from Tahiti.

By 1901, Paul Gauguin had past his half-century mark and was feeling his age. He found himself completely spent, creatively, physically, and financially. In one last bid at creative inspiration, he sought seclusion in the remote wilds of the island of Hiva Oa in the Marquesas Islands chain, almost 900 miles northeast of Tahiti. Appropriate for an escapist such as Gauguin, the Marquesas are among the most isolated islands in the entire world.

And it looks like the move worked. Settled in a hut he named “the House of Pleasure,” he produced quintessentially Paul Gauguin art for 18 months, tirelessly drawing, painting, and writing.

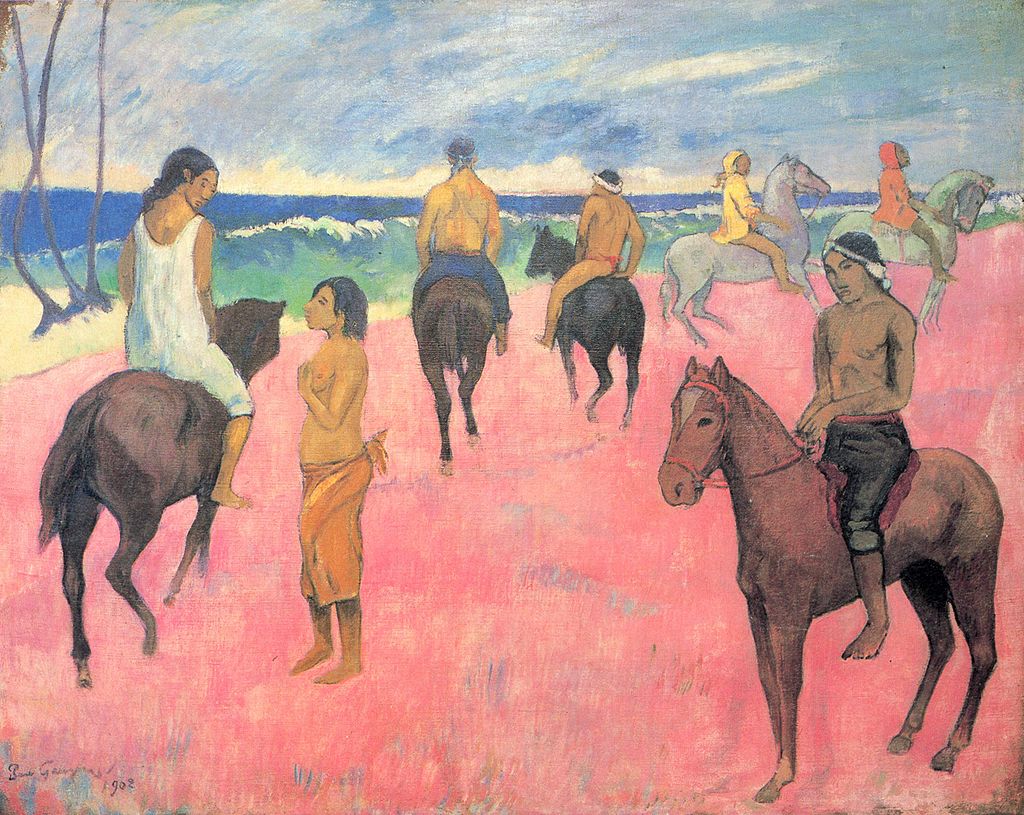

Paul Gauguin, “Cavaliers sur la plage (II)” (“Riders on the Beach (II)”), 1902, credit Wikimedia Commons

One of the last Paul Gauguin paintings was “Cavaliers sur la plage (II)” (“Riders on the Beach [II]”), created in 1902. This shoreline equestrian scene is thought to be a depiction of Hiva Oa. Curiously, each figure on horseback seems to be making progress down the beach, save one, who is kind of breaking the fourth wall, his steed turned around as he looks right at the viewer. It is another piece of Paul Gauguin art that demonstrates his skill with color. Most of the scene is taken up by the pink-colored beach, topped by a beautifully-rendered sky that blends blue, yellow, and green.

Paul Gauguin became debilitated by syphilis and died of heart failure in May of 1903 at 54. He is buried in Hiva Oa, his grave topped by one of his favorite sculptural creations, a depiction of the Tahitian god of mourning.

Are you feeling inspired to create art after reading about Gauguin? Make sure to shop set below for your next creation