Happy birthday Vincent Van Gogh! We figure the best 168th birthday present for this legend is to tell the truth of his life as best as we can. Many of the myths about Vincent’s life are attributed to the 1934 novel “Lust for Life” and its 1956 film adaptation. Nowadays, scholarly study has enabled us to get close to separating fact and fiction. It was a life filled with beautiful art but was also harrowing and heartbreaking at times.

The very birth of Vincent Van Gogh was marked by tragedy. This exact name was given to a stillborn baby brother born in 1852. One year later, on March 30, 1853, the Vincent Van Gogh that would survive was born in the Dutch village of Groot-Zundert. His father was Pastor Theodorus Van Gogh, and mother, Anna Carbentus.

Among his five siblings, Vincent would form a lifelong bond with brother Theo, who was four years younger. Unfortunately, Vincent’s mother was unable to move on from the death of the first Vincent Van Gogh, a despondency that would prevent the surviving Vincent from truly connecting with her, which greatly pained him. Anna did have some positive influence on Vincent, though. She instilled a love of the flora and fauna of nature within him, and taught him to draw and create watercolors. Vincent Van Gogh’s immersion into the world of art truly began at the age of 15. He had to leave school and get a job to help support the family, so his uncle hired him on at Goupil & Company, Europe’s largest art dealer. It was based in The Hague, a coastal Dutch city 55 miles north of Vincent’s hometown. The city was considered the center of the Dutch art movement, which meant an abundance of work by some of the world’s most talented artists for him to view. He loved it.

Goupil transferred him to their London gallery in 1872, and this period is considered the happiest of his life. Unfortunately, in what would become a familiar pattern, Vincent self-sabotaged with his hotheadedness, and the company eventually fired him. Vincent Van Gogh explored a life of religious devotion, but it just wasn’t a good fit. The last straw was when he was preaching in a poor coal-mining town in Belgium, and horrified church leaders with his drastic sacrifices of comfort. With nowhere else to turn, he decided to preach on his own and in his own way—through art. And so began the era in which the famed Vincent Van Gogh paintings were created. It was 1880, and he was 27. After Vincent informed his brother of his art aspirations, Theo became his unfailing benefactor. And it wasn’t just financial assistance. Theo was an esteemed art dealer with Goupil, and he would give an avenue for Vincent to publicly display and sell his work.

By 1885, Vincent Van Gogh was studying shoulder-to-shoulder with some of the greats in Paris, living in Theo’s apartment. The artist’s brother had reoriented him, after declaring that his dark, Rembrandt-like painting “The Potato Eaters” would never sell in Paris. Theo pointed to the groundbreaking work of artists like Monet, Lautrec, and Gauguin, and the artist was blown away by their manipulation of light and time with vivid colors. Vincent Van Gogh was incredibly driven and scoffed at those who didn’t work as hard as he did. His argumentative nature rubbed many of his Paris associates the wrong way, but Theo spoke well of his brother, insisting that he was genuinely a good person.

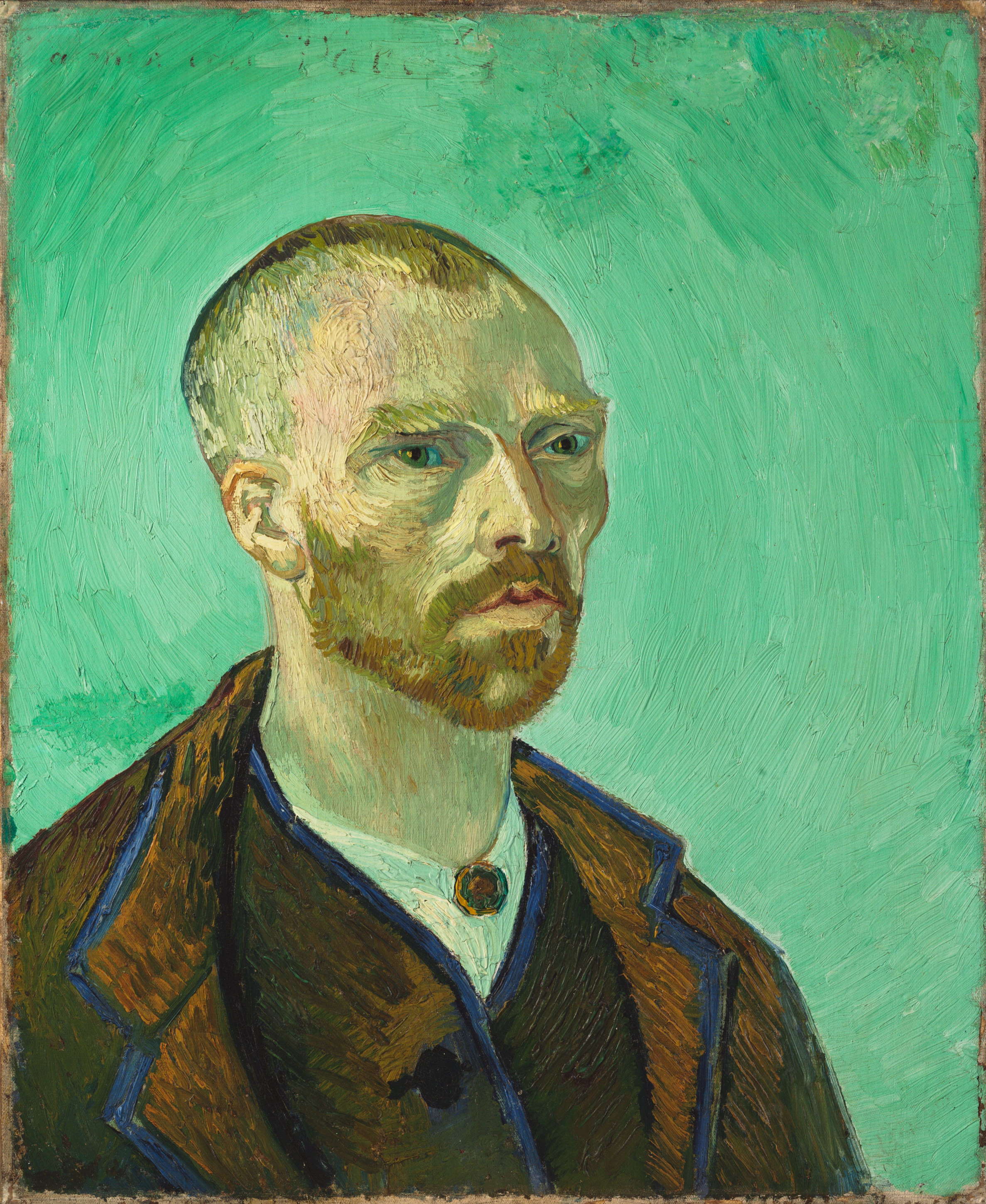

Paul Gauguin did, however, strike up a friendship with Vincent. They talked passionately about their artwork, often while consuming absinthe, a liqueur that can cause hallucinations in large amounts. They also swapped portraits of themselves, and one particular Vincent Van Gogh self-portrait revealed his Japanese art influence. He cast himself as a kind of Buddhist monk, with unmistakably almond-shaped eyes. A big aspect of Japanese art that influenced Vincent was the fact that each and every brush stroke is significant.

“Self Portrait (dedicated to Paul Gauguin),” 1888, Wikimedia Commons

“Self Portrait (dedicated to Paul Gauguin),” 1888, Wikimedia Commons

It was the draw of Japan that led Vincent to Arles, an ancient city in the south of France. A journey to the Far East wasn’t feasible, but when Toulouse-Lautrec told him that the light in Arles was comparable to Japan, Vincent was on his way, arriving in February 1888. The distinctive light of the city and countryside soon shone from Vincent Van Gogh’s works. A few months into his stay, Vincent moved into his beloved Yellow House. It was perfect. The rooms had an abundance of light, and there was room for friends to visit.

“The Yellow House (The Street),” 1888, Wikimedia Commons

“The Yellow House (The Street),” 1888, Wikimedia Commons

At this point, most of Theo’s monthly allotment of francs went to rent, paint, and canvases, which didn’t leave much for food. Vincent was mostly consuming just bread, coffee, absinthe, and tobacco. Alarmingly, he began drinking and inhaling turpentine, and eating lead-based paint, both of which are toxic. But Vincent still managed to create great art. “Sunflowers” was painted here. In a supreme example of “less is more,” the work is composed of just three shades of yellow. Vincent Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” is a symbol of “gratitude,” as he put it, an emotion experienced by Vincent as Gauguin came to live with him in Arles. Theo was worried about his brother’s condition and provided Gauguin with a stipend as an incentive to make the move.

“Sunflowers,” 1889, Wikimedia Commons

“Sunflowers,” 1889, Wikimedia Commons

Barely a month into his stay, the arguments began, culminating in one of the most infamous incidents in Vincent’s life—the severing of his left ear. There are many conflicting theories about what happened (including the exact amount of his ear that was sliced off), but this account is a strong candidate for the truth:

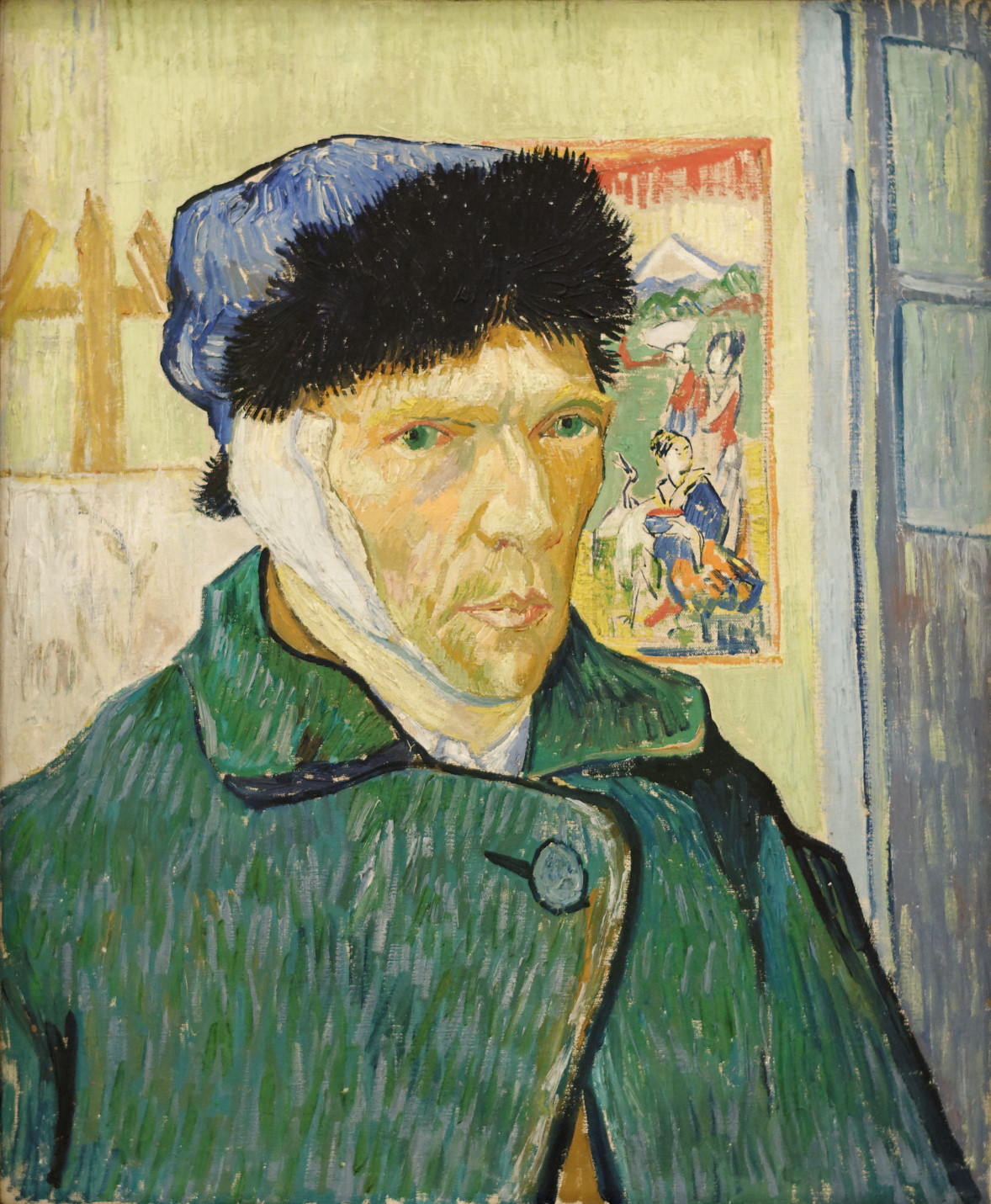

During one especially furious argument a few days before Christmas, 1888, Gauguin stormed out. While walking down the street, he suddenly realized that Van Gogh was following him, brandishing a razor. After a silent standoff, Vincent went back to the Yellow House, and Gauguin sought other lodgings for the night. A few hours later, a prostitute at a local brothel received a ghastly gift from Vincent Van Gogh—his severed left ear. He departed, bleeding heavily, and was found by authorities the next morning. Eventually he would commemorate the maiming with “Self-portrait with bandaged ear.”

“Self-portrait with bandaged ear,” 1889, Wikimedia Commons

“Self-portrait with bandaged ear,” 1889, Wikimedia Commons

The artist was immediately admitted to the Hotel-Dieu Hospital, weakened from blood loss, and experiencing delirium and seizures. He was released in January, but soon returned. Then the populace of Arles turned against him, circulating a petition declaring him a danger to the public. Shunned, he left the city for an asylum near Saint-Rémy-De-Provence and began painting there in May 1889. Despite unending difficulty, Vincent Van Gogh was actually starting to get noticed. In November 1889, he was given the opportunity to display his paintings in Brussels alongside works by Renoir, Cezanne, and Lautrec. Among the six was the monumental “The Starry Night.”

“The Starry Night,” 1889, Wikimedia Commons

“The Starry Night,” 1889, Wikimedia Commons

Vincent Van Gogh’s “The Starry Night” is probably one of the world’s most famous works of art. It is a kind of composite view from his window at the asylum. Vincent’s favored theme of nature is prominent with celestial objects, trees, and mountains, with the village nestled within. Not only is he depicting a scene, but also conveying the meaning and emotion that the elements of the scene instill in him. His deliberate brushstrokes imbue a kind of glow to the pictorial elements.

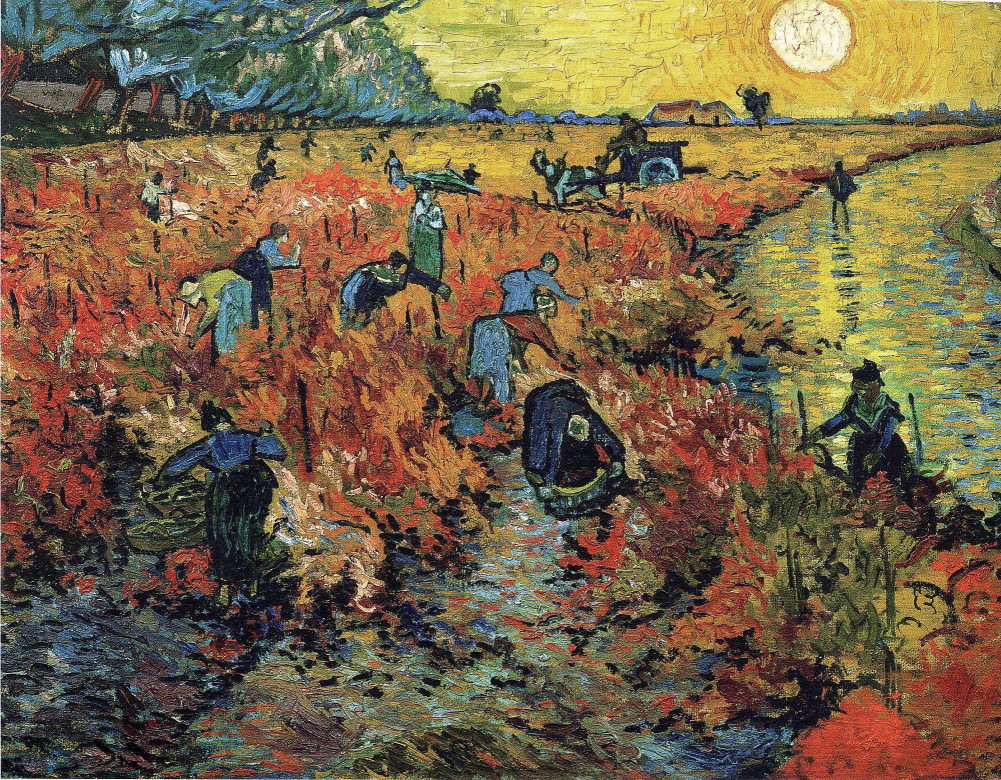

Then Theo managed to sell one of Vincent’s paintings for 400 francs, “The Red Vineyards near Arles,” which depicted the labors of vineyard workers. It would be the only painting sold in Vincent Van Gogh’s lifetime.

“The Red Vineyard,” 1888, Wikimedia Commons

“The Red Vineyard,” 1888, Wikimedia Commons

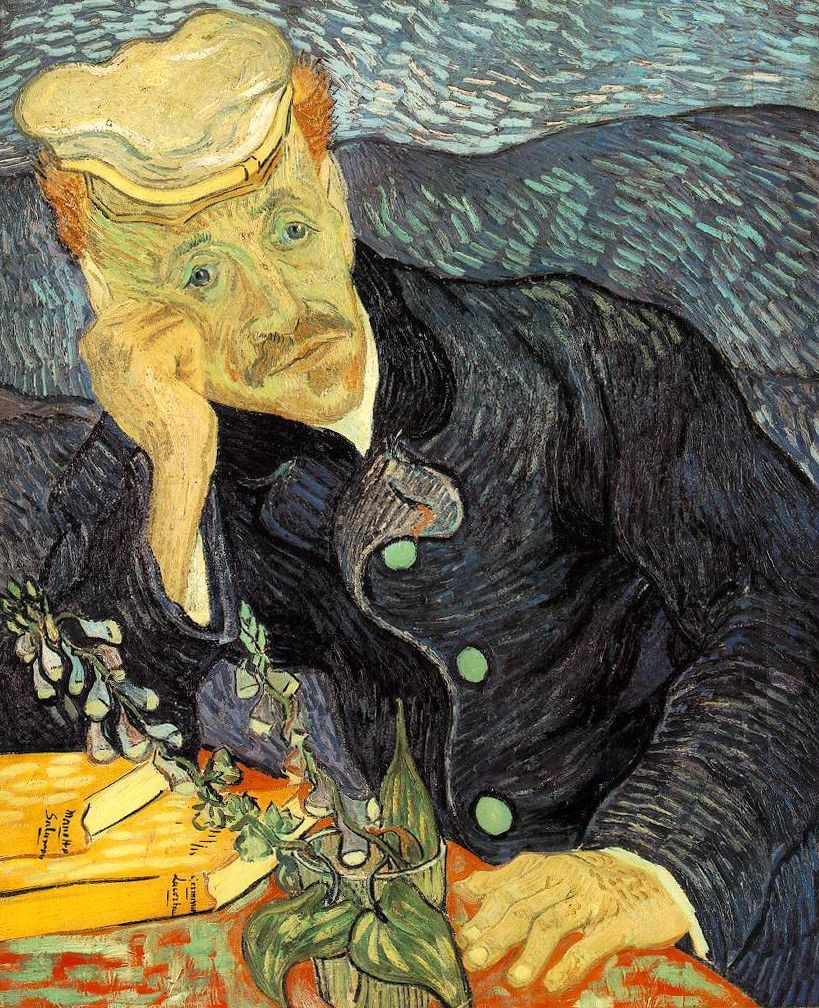

As 1890 progressed, Vincent ended up in Paris, but the bustle of the city was anxiety-inducing. Arrangements were made for lodging in Auvers-Sur-Oise, 20 miles outside of Paris. Vincent was put under the care of Dr. Paul Gachet. Vincent Van Gogh couldn’t know it at the time, but one of his paintings with Dr. Gachet as the subject would sell for $82.5 million in 1990, a record price paid for a work of art at auction.

“Portrait of Dr. Gachet,” 1890, Wikimedia Commons

“Portrait of Dr. Gachet,” 1890, Wikimedia Commons

In the spring of 1890, Theo told Vincent to be more careful with spending his monthly allowance, as the artist’s brother was having financial issues. This shook Vincent Van Gogh to the core, as he thought their “money-for-paintings” relationship was in jeopardy. The prospect of Theo losing faith in him became too much to bear.

On July 27, 1890, Vincent went out to the wheat fields in Auvers-Sur-Oise to paint in the early morning. At some point, he produced a pistol and shot himself in the chest. The wound was not immediately fatal, and he was found still alive in his room that night. Theo was sent for, and Vincent died in his arms in the early morning hours of July 29. He was 37.

Theo’s health then took a turn for the worse, and he died six months later. They are buried side-by-side in Auvers.

All told, Vincent completed around 2,100 distinct pieces of art in the decade he was a full-time artist, including about 860 oil paintings.

Vincent Van Gogh’s posthumous fame can be traced back to Theo’s widow Johanna, who painstakingly collected and catalogued Vincent’s artwork and letters.

Vincent has the reputation as a “mad genius” with his works being a kind of visual representation of insanity. After all, signs of clinical depression, psychosis, and bipolar disorder have been gleaned from his letters. In actuality, experts consider him at his sanest when he was painting, and he put considerable careful thought into the process. And surely, Vincent Van Gogh himself would want us to pay more attention to his masterworks than his mental state.

6 comments

Interesting truthful insight of one of art history’s greats!