The Mexican artist Frida Kahlo was an incredible artist known for her vividly colored self-portraits depicting death, identity and the human body in all its forms. While she may not have wanted to be considered a surrealist, Kahlo’s work often takes viewers into the recesses between reality and dreams, connecting the conscious and unconscious. Kahlo’s paintings and personality lifted her profile to the leagues of an iconic artist. Even after her death, she continues to inspire new generations of artists to explore their craft.

Born Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón on July 6, 1907 in Coyoacán, Mexico, Kahlo found herself torn between her conflicting identities. Her German father was of Jewish and Hungarian descent while her Mexican mother was a devout Catholic with Spanish and Native American heritage. In this way, Kahlo would go on to explore her dueling ethnicities, one being the colonial European ancestry and then her indigenous Mexican roots. Her home was known as La Cada Azul (The Blue House), and she shared it with her four sisters. During her childhood, she witnessed The Mexican Revolution, which began in 1910 when Kahlo was three years old, although later in life she would say she was born in 1910 to associate herself with the revolution. In any case, men fighting in the revolution would vault themselves into Kahlo’s family backyard and make lunch for them.

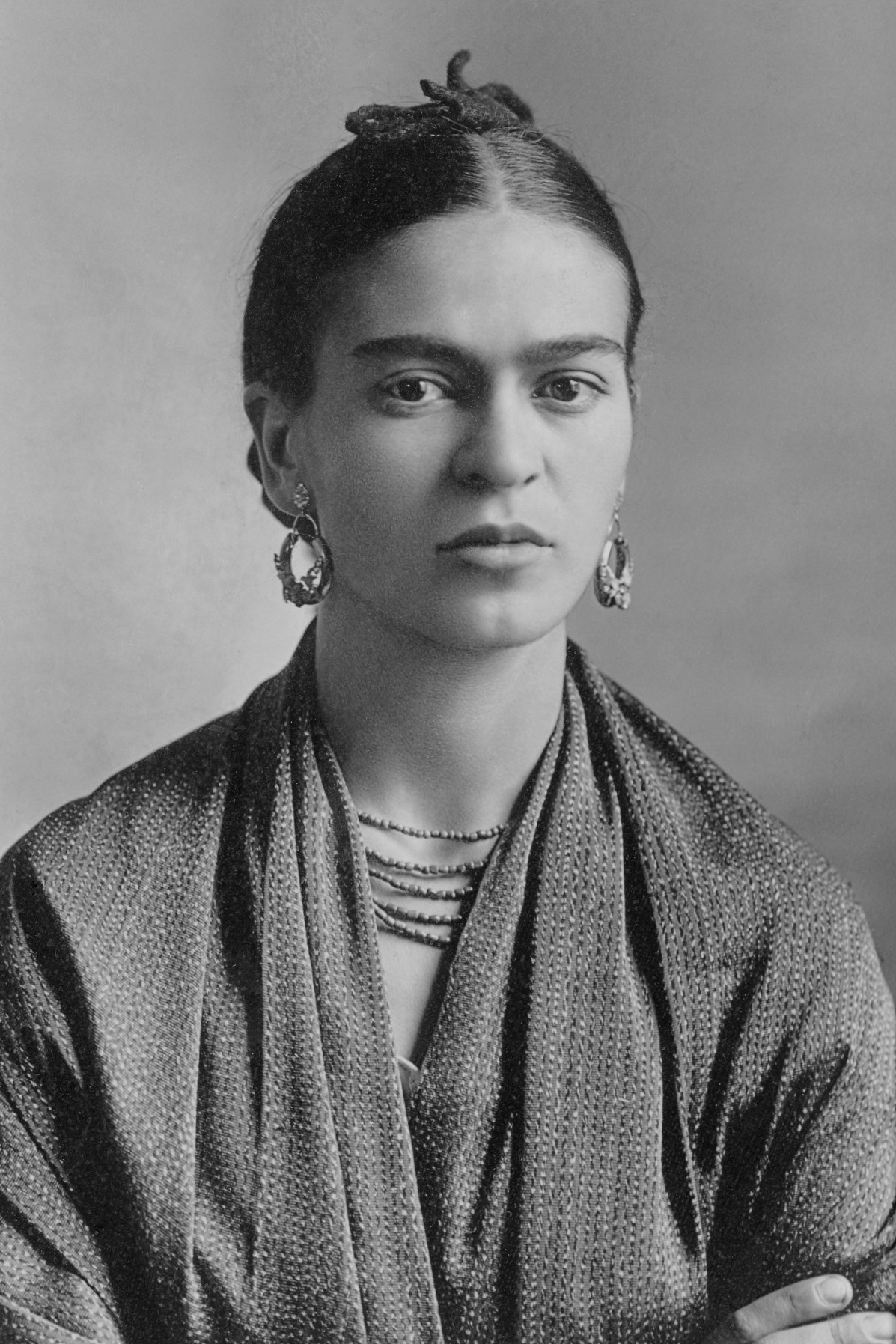

Frida Kahlo by Guillermo Kahlo, Wikimedia Commons

As Kahlo grew, she experienced several formative obstacles that would inform her work as an artist later in life. First, she contracted polio at age six. This caused her right leg to be smaller than her left, and gave her a lifelong limp. She would start to wear long skirts to hide her legs. She may have possibly suffered from the congenital disease spina bifida, which would have impacted her spinal and leg development. One of the scariest moments of her early life came while she was attending school in 1925. Kahlo and Alejandro Gómez Arias, her first serious boyfriend, boarded one bus, and then got off to find an umbrella Kahlo had misplaced. Then they got onto a second bus that was more crowded, and as the bus tried to pass an electric streetcar that was coming toward them. The streetcar crashed into the side of the bus, dragging it several feet and killing several passengers instantly while others died later from their injuries. Arias escaped with minor injuries, but an iron handrail had impaled Kahlo through her pelvis, as she said, “the way a sword pierces a bull,” puncturing her abdomen and uterus, breaking her spine in three places and her right leg in 11 places, among other injuries. She had to be in the hospital for one month, have additional surgery and was bed ridden for several months back home. At this time, she took up painting using an overhead mirror in her bed’s canopy to paint her first self-portraits. One of her early paintings included “Self-Portrait Wearing a Velvet Dress” in 1926.

Once Kahlo had healed, she joined the Mexican Communist Party and met muralist Diego Rivera. She asked him for advice on how to pursue an art career, and in turn he encouraged her talent. The two fell in love and married in 1929. At the start of their marriage, Kahlo took an interest in Mexican folk art. She began wearing the traditional Tehuana dress that consisted of a floral headdress, gold jewelry, loose blouse, and a long ornate skirt, as seen in her painting “Freida and Diego Rivera”,1931. She was, at least image-wise, every bit “the traditional Mexican wife.” Yet, she and Rivera endured a turbulent marriage, divorce and remarriage and many extramarital affairs, including Rivera cheating on Kahlo with Cristina, her younger sister.

"Las dos Fridas" by Frida Kahlo, Wikimedia Commons

Kahlo experienced these and other interpersonal challenges that would inspire her art. While she traveled with Rivera in the United States for his commissioned murals, Kahlo experienced a couple of challenging pregnancies, including a miscarriage in Detroit. She also lost her mother around the same time. During this period, she painted haunting works including Henry Ford Hospital in 1932 and My Birth in 1932, which is part of a series in which she depicts giving birth to herself.

FridaKahlo.org shares the possible inspiration behind this painting and its avid collector:

“Although this painting was painted in the style of an "ex-voto retablo", nothing was written on the unfurled scroll at the bottom. Maybe she felt she cannot describe her feeling about a woman undergoing childbirth. This painting may have also been influenced by a 16th Century sculpture of the Aztec Goddess Tlazolteotl giving birth to an adult male warrior. Popstar Madonna collected this painting. In an interview with Vanity Fair [in 1990], Madonna said she used this painting to tell who is her friend and who is not. "If somebody doesn't like this painting", Madonna said, ‘then I know they can't be my friend’.”

After their American tour, Kahlo and Rivera returned to Mexico in a home with two separate living spaces with an adjoining bridge. In this home, Kahlo began working on her first solo exhibition, which was held at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York. It was a hit and Kahlo had subsequent exhibitions around the world, including Paris. In 1938, Kahlo became the first 20th century Mexican artist to have work included in The Louvre with her painting The Frame.

In addition to her life, Kahlo found inspiration in her own garden. In the 2015 exhibit “Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life,” at the New York Botanical Garden, lush plants from Mexico were a creative wellspring for the artist, as reported by The New Yorker:

“Kahlo’s gardening was of a piece with her art, in asserting a nationalist mythos that extended even to her menagerie of pets: monkeys, parrots, turkeys, an eagle, and a pack of dogs that included Mexican hairless Xoloitzcuintles. What Rivera did on a monumental public scale, in murals picturing Mexico’s storied past and hoped-for future, Kahlo performed—and lived—privately. Even some of the nonnative plants in her garden told apposite stories. Calla lilies came to Mexico with slaves from Africa, and Chinese chrysanthemums arrived aboard Spanish galleons. By today’s gardening standards, not much of the show’s flora is particularly exotic. Even less is what you could call understated. Like everything else about Kahlo, her horticulture commands attention and rewards it with jolts of vicarious, insatiable ardor, if you open your eyes, mind, and heart to her.

Kahlo today inhabits international culture at variable points on a sliding scale between sainthood and a brand. The Botanical Garden show, besides being beautiful, can seem either reverential or exploitative. It’s really both, to a degree beyond the institution’s previous star-powered exhibitions devoted to the gardens of Charles Darwin, Claude Monet, and Emily Dickinson. Like those shows, this one combines scholarly integrity, aesthetic flair, and a calculated occasion, as if any should be needed, for a visit to the two hundred and fifty acres of Eden in the Bronx. Uniquely, Kahlo’s persona blended profound emotion and defiant vulgarity. The world has taken her up at both extremes. Her spirit vibrates in the greenhouse air. But it can’t make you forget that, for twenty-two bucks at the gift shop, you can become the owner of a Frida oven mitt. Among modern paintings, only Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” rivals Kahlo’s self-portraits as an object of alternating awe and burlesque: a template for kitsch that can’t wear out, because the authenticity of the original will never cease to provoke and disturb.”

Portrait of Mexican painter Frida Kahlo, Wikimedia Commons

In 1950, Kahlo’s health issues began to take over her life. She was diagnosed with gangrene in her right foot and then spent nine months in the hospital. She was in and out of hospitals until her death in 1954. Before her passing, she had this to say about death: “I hope the exit is joyful. And I hope never to return.” Kahlo turned her lifelong pain into beautiful paintings. Through her own physically tormented time on earth, she endured and created some of the world’s most incredible works. Today, her memory and work is a testament to following your own path through every obstacle.

6 comments

Very interesting article about Frida Kahlo.