Table of Contents:

- Dada—Surrealism’s Direct Ancestor

- What is Surrealism?

- Surrealism at a Glance

- Surrealist Artists and their Works

Dada—Surrealism’s Direct Ancestor

“Well, that was surreal” you may say after a weird experience. You have the surrealist art movement to thank for that expression’s place in modern culture.

But before diving into surrealism, it is vital to understand dada, its direct ancestor. At their core, surrealists, and dadaists drew from the condition of the soul and state of the senses, rather than a specific technique in a particular style.

Dada was born in early 1916 in Zurich, Switzerland. World War I was raging and the neutral country became a refuge. The Cabaret Voltaire, and later other art-friendly venues were opened in the city and artists and writers, many escapees from the warring countries, flocked to these locales. Anti-war sentiment, and opposition of governmental and social conditions that led to the war in artistic form was common. They blended humor, irreverence, irony, and an intense dislike of the bourgeois. Chance replaced rigor, and the meaning of art itself was brought into question. Dadaists saw no separation between art and life, or the artmaker and the viewer.

Dada concepts spread once World War I ended, but Zurich’s dada scene soon imploded. During an April 1919 dada gathering, the group’s trademark confrontational readings, speeches, and performances purposefully incited a riot. It was motivational art at its darkest. Soon after, dada leader and founding member Tristan Tzara journeyed to Paris and met with French writer and poet André Breton, and they began exploring proto-surrealistic ideas.

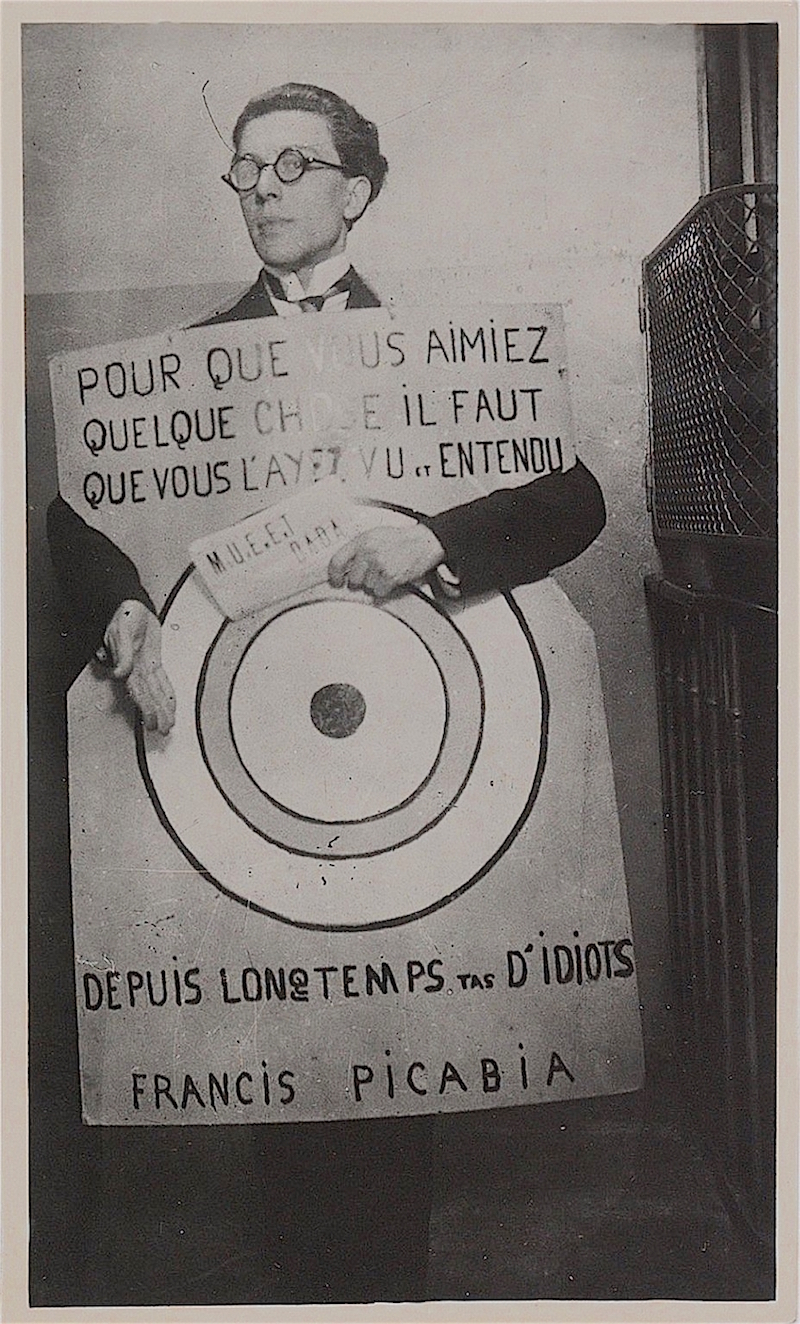

André Breton at a 1920 dada festival, credit Wikimedia Commons

What is Surrealism?

Breton was dubbed surrealism’s “pope.” He co-founded it, led it, and was its prime theorist during its initial rise.

The learned young man was scarred by the horrors that he witnessed as a member of the French army medical corps during World War I. Breton became anti-war, and explored psychoanalysis founder Sigmund Freud’s theories about the unconscious. An interest in dada soon gave way to the construction of what would become surrealism.

In 1924, Breton made the movement official with the “First Surrealist Manifesto.” In it, he defined surrealism as “Pure psychic automatism by which it is intended to express, either verbally or in writing, the true function of thought. Thought dictated in the absence of all control exerted by reason, and outside all aesthetic or moral preoccupations.”

Two major focuses of surrealism are the workings of the unconscious mind and dreams. Regarding the unconscious, it is seen as the source of irrational thoughts that are not always pleasant. Breton felt that ignoring or repressing irrational thoughts makes people, and thus, society, imbalanced—which can lead to war. To create more balance, Breton wanted to explore and liberate these irrational thoughts. Regarding dreams, Breton and the surrealists believed in Freud’s assertion that the unconscious mind communicates with the conscious self in dreams via symbols.

Automatism was seen as an important way to tap into the unconscious. Basically, the surrealist became a kind of “recording device,” documenting whatever sprang from the unconscious, and trying not to resist the flow. For creators of surrealism artworks, automatism could be happening in the medium in real-time, or noted and explored later. Surrealist art could be hyper realistic, and utilize such mediums as collage, decals, grattage, and frottage. A work could be in any one of these mediums, or a combination of them. There wasn’t one overriding style or technique.

Many three-dimensional surrealism artworks borrowed from the dada concept of the “object,” which refers to repurposing an object to make it into a work of art. Surrealists called this “dépayesment” (“estrangement”). One must look upon the object as if you are seeing it for the first time, by removing it from a familiar context. Surrealists were also fascinated with the possibilities of photography, seeing its mechanical nature as a form of automatism. They embraced filmmaking, a medium more akin to dreams, which unfolded over time, and weren’t static like a single piece of art.

Eventually, Breton began autocratically running the surrealist movement like a political collective, changing “official” surrealist axioms and aims, and even “expelling” artists whose perspectives displeased him. This didn’t stop the increasing embrace of the art world, though. Right before World War II in 1938, the movement had one of its biggest moments in the sun with the International Exhibition of Surrealism, held in Paris. Three hundred works were on display, created by over 60 artists from 15 countries.

It could be said that after World War II, the surrealist baton was passed to Spanish artist Salvador Dalí. In many ways he kept the themes, techniques, and imagery of surrealism alive in the art world, and public eye all the way to the present.

Surrealism at a Glance

Regardless of technique or medium, surrealism artworks use some recurring aspects in dream/unconscious representations that the viewer can look for:

- Juxtaposition: There may be two elements that traditionally aren’t associated with each other.

- Dislocation: A familiar element might be removed from its conventional context.

- Transformation: A pictorial element appears to be one thing at first glance, but when examined closer, turns out the be something else. For example, a face may turn out to be bouquets of flowers.

- Shock: Does a particular work of surrealist art make you feel uncomfortable? That’s probably by design.

- Symbolism: An artistic element in a work seems innocuous, but can actually have a deeper meaning, as an expression of the unconscious.

Surrealists and their Works

The oeuvre of important surrealist artists is vast, so the focus here will be on their connection to the movement, and some of the works that came out of that.

Marcel Duchamp: This Frenchman bridged the gap between Zurich dada and Paris surrealism, though he didn’t identify with any one group.

Duchamp pioneered the “readymade,” his conception of the dada “object.” Perhaps the most infamous readymade was “Fountain,” a signed urinal submitted to an art show in 1917.

Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain” (1917), credit Wikimedia Commons

His magnum opus was “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even,” or “The Large Glass,” a sculptural assemblage that was worked on between 1915 and 1923. On two panes of glass over nine feet tall, Duchamp depicted a mechanical, insect-like “Bride” having an amorous encounter with nine “Bachelors” represented by what he called “Malic Molds.” And in true dada/surrealist fashion, when the glass was broken during transport, Duchamp saw it as a “chance” element in the composition.

Duchamp was a legend among the younger surrealists, and played an important role in the aforementioned International Exhibition of Surrealism.

Joan Miró: Independent from surrealists, he would see poetry and painting as two sides of the same coin, and he explored automatism. Miró moved from his native Spain to Paris and befriended Breton, who considered him important in conceptualizing surrealism.

One of his major explorations was with “biomorphism,” a way to represent the unconscious, using biological patterns and shapes from nature. Miró’s “Dutch Interior I, Summer 1928” is a characteristic example. This surrealism painting is a deconstruction of 17th century Dutch artist Hendrick Martensz Sorgh’s traditionally-executed “Lute Player.” Miró “biomorphs” the lute player and his instrument into a variety of bulbous and angular shapes. Other pictorial elements become psychedelic shapes imbued with symbolism.

Surrealist Painter Juan Miró in His Workshop. Photo by Alain Dejean/Sygma via Getty Images

René Magritte: He is one of the most revered artists to come out of Belgium in the 20th century. His trademark bowler hat and stylish dress appeared both on his own self and in many of his works.

Unlike fellow surrealists who drew from a kaleidoscope of techniques, Magritte consistently worked in a relatively straightforward, illustrative surrealism painting style.

When Magritte lived in Paris from 1927-1930, he became acquainted with Breton and the surrealists. Their influence had him adding strange organic forms to his surrealism paintings, and delving into themes of madness and hysteria.

Right after the end of World War II, Magritte broke with Breton due to the what he saw as surrealist elements in the Nazi regime. But that didn’t end the use of his iconic themes. For example, in 1953’s “Golconda," where a number of well-dressed gentlemen in bowler hats can be seen as either falling like rain, floating like balloons, or suspended in mid-air.

Visitors looks at a painting of the Belgian artist Rene Magritte at the press opening of the new Margitte museum in Brussels on May 20, 2009, Getty Images

Salvador Dalí: His flamboyant lifestyle and distinctive moustache made him instantly identifiable. Dalí was younger than Breton and his ilk, but shared much of the same interests, and saw early surrealist works as motivational art.

By the time he made it to Paris in 1926, and started making surrealist connections, the movement was on rocky footing. Dalí, bursting with ideas and enthusiasm, revitalized it.

Dalí got Breton’s attention in 1929 with the short film, “Un Chien Andalou” (“An Andalusian Dog”). The most notorious moment was when a woman’s eye appeared to be slashed with a razor.

Dalí’s morphing of his innermost self into sublime pieces garnered much public acclaim. But in the runup to World War II during the ‘30s, Dalí had an ideological split with surrealists, as they went back to serious politicizing. Dalí moved to New York to get away from the war, and because of his efforts, the general American public became aware of surrealism. And he gave it a fun vibe.

A prime example of Dalí’s style is 1931’s “The Persistence of Memory,” one of the most recognized pieces of art in history.

Salvador Dalí’s “The Persistence of Memory” on display at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Photo by Felix Hörhager/picture alliance via Getty Images

The surrealism painting is hyperrealistic, but also irrational. The hard permanence of the cliffs contrast with the soft timepieces in the foreground. Dalí was aware of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, which stated that time itself was not fixed, thus, the malleable timepieces. It is thought that Dalí himself makes an appearance in the work, as a melted, sleeping face lying on its side.

Pablo Picasso: A prolific titan of 20th century art, Pablo was also a surrealist for a time. Breton even declared him “one of us” in print. At the beginning of the 20th century, Picasso was one of the founders of cubism, It was a revolutionary painting style that melded different viewpoints of a person or object into one highly geometric representation. Cubism never really left his works, so Picasso’s most famous work, 1937’s “Guernica” utilizes elements from both styles.

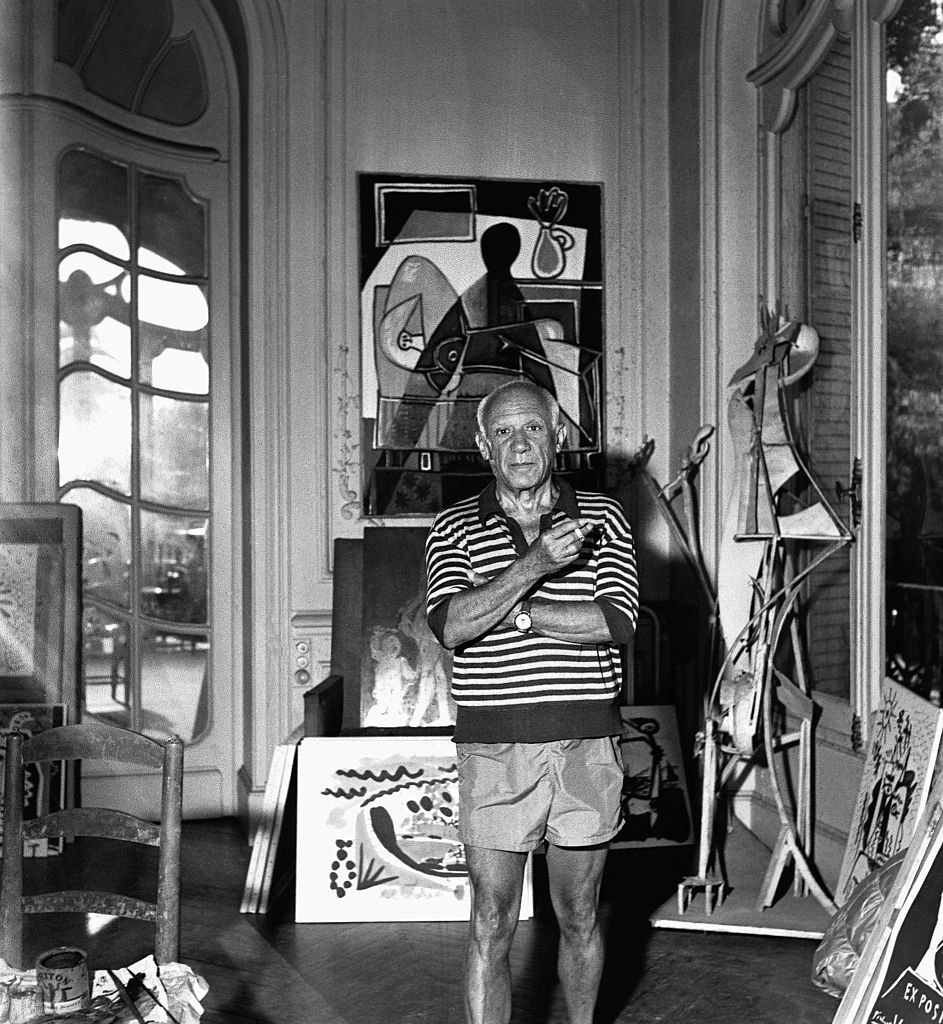

Spanish painter Pablo Picasso, surrounded by artworks, at his villa La Californie in Cannes in 1955. Photo by © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

This mural-sized oil on canvas is an anti-war piece painted in response to the aerial bombing of the Spanish town of the same name. The cubist multi-perspective is evident, as is the unflinching dream-turned-to-nightmare surrealist expression.

The sheer awfulness of war is seen in the jumble of figures at the center, each clearly traumatized, in pain, or both. Civilian, soldier, and animal writhe, and an electric light is presented next to an oil lamp, seeming to convey that there is both good and bad in societal progress.

Surrealism art proves that the unconscious and dreams are compelling sources for artistic inspiration, so next time you fall asleep, make sure you have a notebook handy to jot down your dreams right when you wake up—it could be fodder for your next masterpiece!