Table of Contents:

- The Beginnings of Contemporary Street Art

- The Expansion of Street Art

- Street Art at a Glance

- Street Artists and Their Works

The Beginnings of Contemporary Street Art

In the 21st century, street art is included in the melting pot of genres that can be found in the mainstream art world, but it wasn’t always this way. Contemporary graffiti (or “hip-hop” graffiti) began as underground and unauthorized street art. Graffiti statements in the 1960s and ‘70s, blossomed in New York City neighborhoods with predominantly black and Hispanic populations. All it took was the newly invented aerosol spray can, artistic vision, and a disdain for the art establishment.

Early street art graffiti centered on the “tag,” an illegally placed stylized signature of the artist. Such artists are called “taggers” or “writers.” The goal? To “get up”—get their tags in as many places as possible and seen by as many people as possible. The person who did the very first tagging is unknown, but it’s been narrowed down to three possibilities: Julio 204 or Taki 183 from the Washington Heights area of New York City, or Corn Bread from Philadelphia.

New York City’s subways and trains soon became canvases for taggers. It was a great way for your urban street art to be seen by scores of people, and the art even took on that sense of motion of a moving train car. Eventually, when it came to ranking the most respected street art graffiti practitioners, there were the subway taggers first, then everybody else.

As the graffiti world expanded, so did the variation of pieces. Tags went from basic to sizable, complex, and colorful, sprawled across whole subway cars. Spray cans themselves were also experimented with. Artists swapped out the regular spray paint nozzles (“caps”), for nozzles from other aerosol cans, like oven cleaner to obtain a particular effect or line width. The “wildstyle” street art graffiti style was born.

The Expansion of Street Art

In the ensuing decades, contemporary street art artists have taken the niche far beyond its freehand spray-painting origins. Two mediums have really taken off: stencils, which are made of paper or cardboard that enables quicker execution of a work, and allows layering when using more than one. Then there’s “three-dimensional sculptural interventions,” usually installed in the middle of the night with the goal of stopping a viewer in their tracks with an improbable situation.

Most significant in street art’s rise is the transferring of in-the-field techniques onto canvas, creating hybrid street art paintings. This would, with much controversy, enable street art to be displayed in galleries, which was sacrilege for a number of street artists. They felt that this “selling out” was counter to the principles of authentic street art. Gallery shows and celebrity hobnobbing was far different from illegally tagging a subway car, one step ahead of the cops.

Street Art at a Glance

Unless you are visiting a street art exhibition, your interaction with the medium will probably result from happenstance. If you notice any of these characteristics in a given work, it’s probably street art:

- It grabs your attention as a shocking or unusual scene

- It can be hard to read if it’s text

- It’s not in a spot where you’ll find conventional art

- It suddenly appears one day

- You might not be able to identify the artist

Street Artists and Their Works

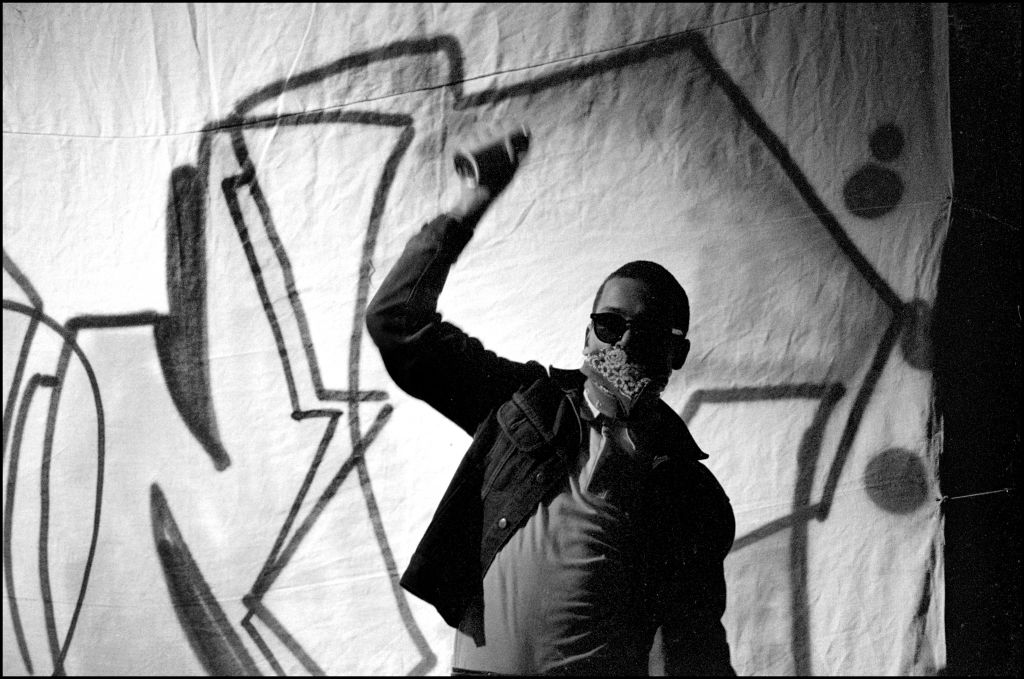

Donald “DONDI” White: He’s a street art founding father. Starting in the mid-70s, White pioneered what became standard street art graffiti aesthetics. His wildstyle pieces, were fairly legible to the layperson, to make it easier to read the text. He was also a fan of intricate patterns. White did a lot of prep work before heading out to his tagging spots, creating detailed conceptualizations in sketchbooks.

American grafitti artist, DONDI (Donald White, 1961 - 1998), at The Venue, London, 27th November 1982. Photo by David Corio/Redferns

Between 1978 and 1980, he created his most famed work, “Children of the Grave” parts 1, 2, and 3. It spanned three entire subway cars, and the name was taken from a Black Sabbath song, a departure from the common hip-hop influence. It was his “DONDI” tag vividly portrayed in his unique style.

White ended up having his pieces in art galleries across the United States, Europe, and Japan when he moved to canvas work by 1980.

Jean-Michel Basquiat: He had a rocket-ship-ride of a career, quickly going from homeless scenester to revered urban street artist. After his tragic death at 27, his posthumous reputation has soared. By the age of 17, he was immersed in graffiti culture, influenced by medical drawings, cartoons, and comic books.

American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960 - 1988), circa 1985. Photo by Rose Hartman/Getty Images

Basquiat’s “SAMO” tag came from a character he created that peddled a fake religion, it stands for “same old sh*t.” It appeared on surfaces in downtown Manhattan starting in 1976, applied by Basquiat and his friend, and was accompanied by textual messages that railed against the establishment, religion, and politics.

When he started exploring canvas work, Jean-Michel Basquiat fell in with the neo-expressionists, who were notable for bringing painting and the human figure back to the contemporary art world.

Much of Basquiat’s work and life was about blending and duality. He blended elements of his African, Latinx, and American lineage, he used both text and image, and would combine contemporary artmaking with historic imagery—one of his recurring characters was a West African griot, basically a local historian relating history through story and song. Regarding duality, he associated with both black and white artists, and explored such themes as wealth vs. poverty, black vs. white, and the inner and outer self.

“Untitled (Skull)” (1981) is a characteristic early Basquiat canvas. The skull is a kind of graffiti-style self-portrait that seems to be grafted together of disparate parts. The skull does not appear to be in a good mood, and the presentation of color and line seems to indicate the visage has been subject to violence.

“Untitled (Black Skull)” (1982) is a recasting of the skull motif, and features an array of symbols. The white skull at the center is seen as a “memento mori,” and its surroundings include a bone, scales, and arrows, all rife with symbolism ranging from the sexual to the unfair criminal justice system. They also hearken back to rural African art.

Keith Haring: After dabbling in cartooning and commercial graphic art, Keith Haring noticed that empty black advertising panels in New York subways would be the perfect place to do white chalk drawings, and he was on his way as a street artist. He created thousands of public works of art featuring his distinctive cartoonish characters and symbols between 1980 and 1985 in locales all over the world, including the Berlin Wall.

Graffiti artist Keith Haring, known for his squiggly doodles of dogs and humans poses for a portrait in September 1986 in New York City, New York. Photo by Joe McNally/Getty Images

He wanted to gain positive attention to his works, so he used cartoon-like forms and symbols, simple shapes, and vivid colors. It was a combination of accessibility and moving social commentary.

There are some Haring works that embody his varying stances on hot-button issues that arose during his life. “Untitled” (1982), an acrylic on vinyl, depicts two figures running toward each other with a heart perched overhead, infused with kinetic lines. The piece is meant to sincerely represent two men in love, a bold gesture for the time.

The “Free South Africa” (1985) poster responds to racist repression in South Africa known as Apartheid. Here, the large black figure towers over the white figure, with the white figure holding a kind of leash that is connected to a collar around the black figure’s neck. The image conveys the minority whites oppressing the majority blacks. This work is actually seen as playing a part in the eventual end of Apartheid.

“Crack is Wack” (1986) is a highly visible rendering of an urban street art painting, an orange-and-black mural painted in Harlem, New York City. It was created right in the middle of the city’s crack epidemic, something greatly concerning to Haring. It features the name of the piece surrounded by symbols representing death and the wasting of money.

“Rebel with Many Causes” (1989) is Haring’s reimagining of the “hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil” motif, in silkscreen on paper, and he is showing how the public isn’t paying enough attention to the AIDS crisis. The AIDS issue hit home for Haring, as he was openly gay and losing close friends to the disease at the time. And, unfortunately, it would end up causing his own death.

Shepard Fairey: This punk rock-loving skateboarder first got attention as an urban street artist when going to art school in Providence, RI. Fairey’s artistic efforts are considered a vital element to modern urban art’s genesis and progression. His name is spoken in hushed tones among street artists, because when it comes to “getting up” as a graffiti artist, they feel that Fairey has won for all time, as no one can “get up” as much as he has.

Shepard Fairey attends Corey Helford Gallery And Sanrio Host Hello Kitty 45th Anniversary Group Show Opening Reception at Corey Helford Gallery on June 29, 2019 in Los Angeles, California. Photo by Presley Ann/Getty Images

Fairey’s “carpe diem” attitude stems from his diabetes diagnosis, that will likely shorten his life. The first time this credo really showed itself was in the late ‘90s, when he ran a graphic design studio in San Diego that specialized in guerilla marketing. He would crisscross the world, performing daring stunts like climbing tall buildings and accessing towering billboards in order to “bomb” a location with posters and stickers. Not surprisingly, such urban street art-oriented acts often landed him in jail, and caused ongoing legal problems.

Fairey’s body of work in posters, stickers, and murals often blends advertisement with propaganda. His imagery can take on tones of pop art’s commerciality, while his geometry is very Russian constructivist.

Funnily enough, the image of famous wrestler and actor Andre The Giant has been a kind of guardian angel for Fairey. It graced a sticker dubbed “Andre The Giant has a Posse” (1989) that Fairey created with no grand expectation, but once it ended up stuck to public surfaces, it got unexpected media attention. The impact of the 1996 “Obey” campaign was huge for Fairey’s urban street art cred. The sticker or stencil is a simplified rendering of Andre’s face above the word “Obey” in Futura font. Fairey said he wanted to present “democratized art” with the appearance of “Obey” in cities across the globe—showing that public spaces can have more than just advertising and government messaging. Fairey was asking bigger questions as well—when someone is told to “obey,” what does that really mean? Why do people accept certain conditions of existence?

Presidential candidate Barack Obama’s face is front and center with “Hope” (2008). The two-term president’s pose exudes positivity and nobility, not unlike John F. Kennedy. And, of course, the color scheme is red, white, and blue. Fairey was inspired to create the work after watching an Obama speech, and approving of the candidate’s political beliefs. He chose the “Hope” caption, in the face of what he saw as hopelessness among American citizens. It was a massive success, and has been placed in the upper echelon of U.S. presidential election posters throughout history.

Banksy: Who is Banksy? Nobody knows. There has been plenty of speculation—he may even be more than one person. What is clear is that his street art graffiti compositions convey messages against war, capitalism, and the establishment. And rarely has someone been so famous, yet still anonymous.

Banksy’s freehand graffiti tag began to appear in Bristol, England in the early 1990s, but it was his stencils that got him first noticed. Banksy has zero regrets about his illegal works, and claimed to be protesting “Brandalism,” a concept of his own creation, which referred to ads and slogans put up by companies that people can’t not see.

By the early 2000s, Banksy began doing “prankster” public interventions, often at traditional art institutions, and would also conduct simultaneous legal and illegal exhibitions. These happenings often skewered the commerciality of art, pop culture, mass media, the wealthy, and politics. The urban street art interventions saw him in New York City’s famed museums, placing alternate versions of already-famous artwork, illegally entering the London Zoo’s penguin enclosure, and painting pro-migrant murals at a Syrian refugee camp in France. And the list goes on.

Then Banksy took artistic destruction to a place it had never gone before, right in the middle of a formal auction. His work “Balloon Girl” had just sold for 1.04 million pounds, and the instant the gavel signaled the sale, an alarm inside the frame went off, and “Balloon Girl” went through a hidden shredder.

His notable public spray-painted urban street art works highlight Banksy’s tendency toward jarring juxtaposition. For example, “Rage, the Flower Thrower” (2005), a stencil and spray-paint work created in Jerusalem, depicts a person looking like he is about to hurl something harmful, but is actually wielding a bouquet of flowers. “Napalm Girl” (2004-05), a screen-print on paper, recasts one of the most famous photos of the Vietnam War, of a naked girl running away from an American napalm attack. She is flanked by none other than Mickey Mouse and Ronald McDonald, quintessential symbols of American capitalism.

Street art is a fascinating genre with a lot of different mediums and techniques to choose from. Just remember, when leaving the canvas behind and taking your artistic implements to the streets, make sure you have permission before making your work public!

Did you get inspired after reading about street art? Okay, so we’re not suggesting you go out and graffiti public walls, but you can create your own mini tag at home using an Arteza canvas and our best-selling acrylic markers. Make sure to shop set below for your creation.